When antibiotics disappear from hospital shelves, it’s not just a supply chain glitch-it’s a life-or-death crisis. In 2024, the U.S. faced its highest number of antibiotic shortages in a decade. Across Europe, 14 countries called the situation "critical." In Kenya, nurses send patients home without treatment because penicillin isn’t available. This isn’t a hypothetical scenario. It’s happening right now, and the consequences are already showing up in emergency rooms, ICUs, and rural clinics.

Why Antibiotics Are More Likely to Run Out

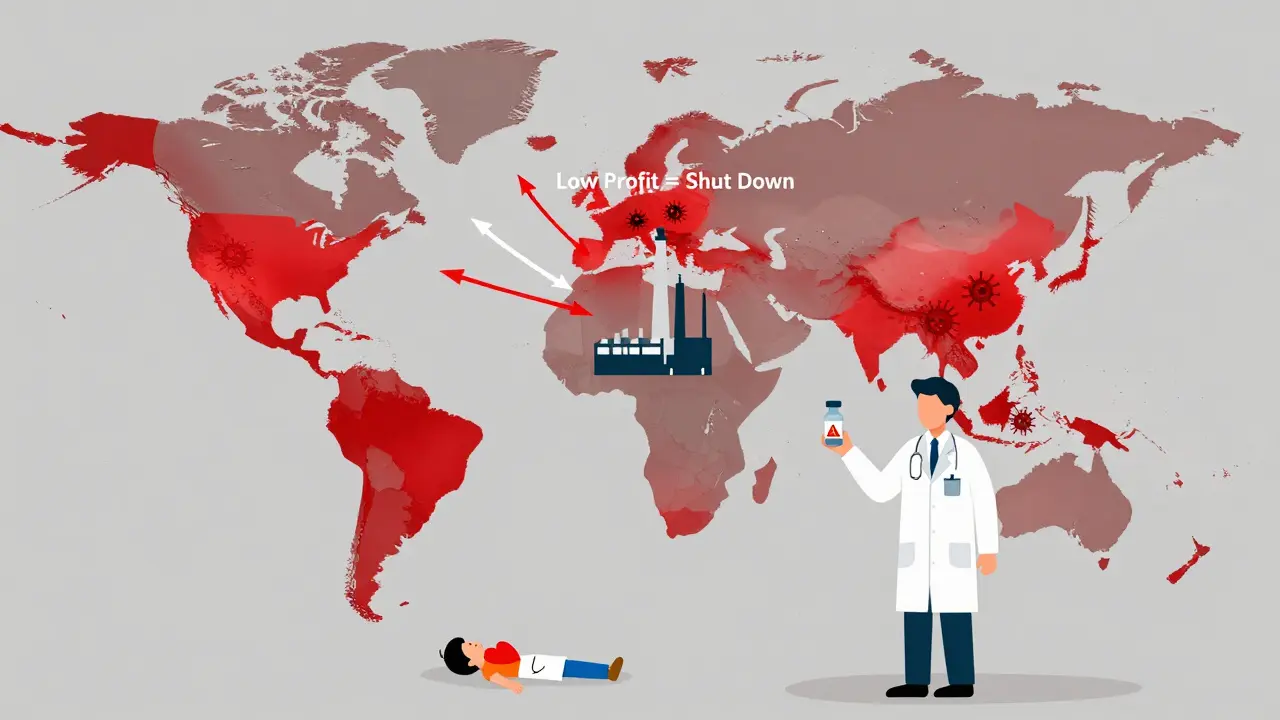

Antibiotics are 42% more likely to face shortages than any other type of drug. Why? It’s not because they’re harder to make. It’s because no one wants to make them. Generic antibiotics like amoxicillin, penicillin, and cefazolin cost pennies per dose. Manufacturers can earn far more by producing cancer drugs, diabetes meds, or even cosmetic injectables. The global antibiotic market grew just 1.2% from 2019 to 2024, while the rest of the pharmaceutical industry grew at 5.7%. That gap isn’t accidental-it’s economic.At the same time, regulatory costs have jumped 34% since 2015. Making sterile injectables requires clean rooms, strict quality controls, and constant inspections. But if you’re selling a vial of penicillin for $0.50, you can’t afford those upgrades. So factories shut down. Or worse-they keep running with outdated equipment, leading to contamination recalls that wipe out months of supply. The European Court of Auditors found that regulatory agencies have failed to enforce standards for these facilities, knowing full well that manufacturers can’t afford to comply.

The Global Picture: Who’s Most Affected

Antibiotic shortages hit hardest where they’re needed most. In low- and middle-income countries, 70% of antibiotics are already inaccessible. The WHO calls this a "syndemic"-a deadly mix of resistance and under-treatment. In South Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean, one in three bacterial infections is resistant to first-line antibiotics. In Africa, it’s one in five. When the only drug that works isn’t in stock, patients die.In high-income countries, the problem looks different but is just as dangerous. The U.S. had 147 active antibiotic shortages by the end of 2024. The UK saw shortages triple after Brexit-from 648 in 2020 to 1,634 in 2023. In the European Economic Area, 28 countries reported shortages, with 14 labeling them critical. Amoxicillin, one of the most common antibiotics, vanished from shelves in early 2023. Usage dropped by 55% in 22 health databases. That didn’t mean people stopped getting infections. It meant doctors switched to stronger, riskier drugs.

What Happens When the First-Line Drug Is Gone

Antibiotics aren’t interchangeable. If you run out of amoxicillin for a child’s ear infection, you might switch to azithromycin. But if you’re treating a urinary tract infection and both amoxicillin and cephalosporins are gone? You’re forced to use carbapenems-antibiotics reserved for the most dangerous, resistant infections. That’s like using a tank to kill a mosquito. And every time you do, you make superbugs stronger.Over 40% of E. coli and 55% of K. pneumoniae are now resistant to third-generation cephalosporins. When those drugs aren’t available, doctors turn to colistin-a toxic, last-resort antibiotic that can damage kidneys. Dr. Sarah Chen, an infectious disease specialist in California, told the APHA forum she had to use colistin for a routine UTI. "It’s not what we want to do," she said. "It’s what we’re forced to do."

Reddit threads from UK and U.S. doctors show the same pattern: rationing, substitutions, delays. One clinician wrote: "We’re now treating strep throat with vancomycin because we don’t have penicillin." That’s not just poor practice-it’s a public health emergency.

The Human Cost: Real Stories Behind the Numbers

Behind every statistic is a person. In Mumbai, a mother waited 72 hours for azithromycin to treat her child’s pneumonia. By the time it arrived, the infection had worsened. The child ended up in intensive care. In rural Kenya, a nurse shared that when penicillin runs out, she has no choice but to send patients home. "We know they might die," she said. "But we have nothing else."These aren’t rare cases. A 2025 survey found that 78% of U.S. hospital pharmacists had to change treatment plans because of shortages. Sixty-two percent reported more patient complications. In hospitals without strong stewardship programs, delays in treatment increased by an average of 48 hours. For sepsis, every hour counts. Delayed antibiotics raise death risk by 7% per hour.

What’s Being Done-and Why It’s Not Enough

Some progress is happening. The U.S. FDA approved two new antibiotic manufacturing plants in January 2025, expected to ease 15% of shortages by late 2025. The WHO launched a $500 million Global Antibiotic Supply Security Initiative in October 2025, backed by G7 nations. The European Commission is rolling out new rules to guarantee minimum stockpiles by 2026.But these are band-aids. The real fix requires systemic change. Right now, companies make money by producing drugs people take for years-like blood pressure pills. Antibiotics are taken for seven days. The return on investment is tiny. Until governments pay manufacturers to make these drugs-even if they’re not profitable-we’ll keep seeing the same cycle: shortage, panic, substitution, resistance, repeat.

Hospitals are trying to adapt. Johns Hopkins cut unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use by 37% during shortages by using rapid diagnostic tests to identify infections faster. California created a regional sharing network that reduced critical shortage impacts by 43%. But these solutions require time, money, and trained staff. Only 37% of U.S. hospitals meet all WHO standards for antimicrobial stewardship. Most are still flying blind.

What You Can Do

As a patient, you can’t fix the supply chain. But you can help slow the crisis. Never pressure your doctor for antibiotics. Don’t take leftover pills. Don’t skip doses. Misuse drives resistance, and resistance makes shortages worse. If you’re prescribed an antibiotic, take it exactly as directed-even if you feel better.Support policies that fund antibiotic production. Advocate for hospitals to invest in stewardship programs. Demand transparency from drugmakers and regulators. This isn’t just a medical issue. It’s a political one. And it’s already costing lives.

The Future: What’s at Stake

Without major intervention, global antibiotic shortages will rise 40% by 2030. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance predicts 1.2 million additional deaths each year from infections we used to treat easily. That’s more than the current annual death toll from HIV/AIDS and malaria combined.The WHO wants 70% of antibiotic use to come from the "Access" group-safe, affordable, effective drugs-by 2030. Right now, it’s 58%. We’re moving in the wrong direction. And every time we delay action, we lose ground to resistant bacteria.

This isn’t about running out of pills. It’s about running out of time.

Why are antibiotics running out when we need them more than ever?

Antibiotics are cheap to produce but offer low profits. Manufacturers focus on more profitable drugs like cancer treatments or diabetes meds. At the same time, strict safety rules for sterile production have increased costs by 34% since 2015, making it harder for companies to stay in business. When factories shut down or get shut down for violations, supply drops-and there’s no quick replacement.

Are there alternatives when antibiotics are in short supply?

Sometimes, but not often. For common infections like ear infections or UTIs, there may be a similar antibiotic. But for resistant infections, alternatives are limited. Doctors often have to use stronger, more toxic drugs like colistin or carbapenems, which drive further resistance. In many cases, especially in low-income countries, there are no alternatives at all.

How do antibiotic shortages affect antibiotic resistance?

They make it worse. When first-line antibiotics aren’t available, doctors use broader-spectrum drugs to cover more types of bacteria. This overuse kills off harmless bacteria and lets resistant strains survive and multiply. For example, using carbapenems for simple infections increases resistance to these last-resort drugs, making future infections harder to treat.

Is this problem only happening in the U.S. and Europe?

No. While high-income countries see shortages in hospitals, low- and middle-income countries face even worse access problems. In Africa and parts of Asia, 70% of antibiotics are already unavailable. People die from infections that should be treatable with a $0.50 pill. This isn’t a supply chain issue-it’s a global equity crisis.

What’s being done to fix antibiotic shortages?

The WHO and G7 nations launched a $500 million initiative to secure antibiotic supply chains by 2027. The U.S. FDA approved two new manufacturing plants in early 2025. The EU is enforcing minimum stock requirements. Hospitals are improving stewardship programs. But these efforts are still too small and too slow. Without guaranteed funding for production, shortages will keep coming.

Can patients help prevent antibiotic shortages?

Yes. Don’t demand antibiotics for viral infections like colds or flu. Always finish your full course-even if you feel better. Don’t save leftover pills for later. Misuse fuels resistance, which makes shortages more dangerous. Support policies that reward antibiotic production. Your choices matter more than you think.

Dan Mack

January 14, 2026 AT 15:56Big Pharma is deliberately causing these shortages so they can sell you expensive new antibiotics later. They don't want you to get better cheaply. They want you dependent. The FDA? Owned. The WHO? A puppet. This isn't a crisis-it's a profit scheme.

Gloria Montero Puertas

January 15, 2026 AT 03:35It’s profoundly disturbing-nay, morally indefensible-that we’ve allowed the commodification of life-saving pharmaceuticals to devolve into a game of marginal returns. The fact that penicillin-a molecule synthesized since the 1940s-is now a casualty of corporate calculus speaks to the terminal decay of our healthcare ethos. Where is the collective shame?

Sohan Jindal

January 17, 2026 AT 02:18Foreign factories are making our antibiotics and they’re cutting corners. That’s why the stuff fails. We need to bring production back to America. No more outsourcing medicine. If you can’t make it here, you don’t get to sell it here. Lock down the plants. Protect our soldiers, our kids, our moms.

Frank Geurts

January 18, 2026 AT 13:23While the systemic underinvestment in essential medicines is undeniably troubling, it is imperative to recognize that the global pharmaceutical ecosystem operates within a framework of regulatory, economic, and logistical constraints. The challenge lies not in moral condemnation, but in the development of sustainable, incentivized manufacturing paradigms that reconcile public health imperatives with fiscal realities.

Arjun Seth

January 20, 2026 AT 10:30Everyone blames the companies but no one talks about the doctors who give antibiotics for colds. You think this is about money? No. It’s about laziness. People demand pills for viruses. Then they get mad when the pills run out. Stop being stupid. Take care of your body. Don’t be a baby.

Mike Berrange

January 22, 2026 AT 07:04The author conflates supply chain vulnerability with corporate malice. There is no evidence of intentional sabotage. The issue is economic disincentive, not conspiracy. Also, the WHO’s $500M initiative is irrelevant without binding production quotas. This article reads like a press release disguised as journalism.

Amy Vickberg

January 23, 2026 AT 22:33I’ve seen this in my hospital. We had to use vancomycin for strep throat last month. It breaks my heart. But I’m hopeful-more hospitals are starting stewardship programs. We’re learning. It’s slow, but change is possible. We just need to keep pushing.

Nishant Garg

January 25, 2026 AT 06:28In India, we’ve lived with this for decades. A vial of penicillin costs less than a chai. But if the local pharmacy doesn’t get the shipment? No one dies instantly-they just suffer longer. The real tragedy isn’t the shortage-it’s that we’ve normalized it. We’ve learned to wait. To hope. To pray. And still, we survive. Maybe that’s the most dangerous part.

Amy Ehinger

January 26, 2026 AT 04:02I work in a rural clinic. We’ve had to reuse syringes when antibiotics run out. Not because we’re careless-because we have no choice. It’s not just about money. It’s about dignity. People deserve to be treated like humans, not statistics. I’m tired of being told to be grateful for scraps.

RUTH DE OLIVEIRA ALVES

January 27, 2026 AT 01:39It is incumbent upon policymakers to institute forward-looking, risk-adjusted procurement mechanisms that ensure the continuous availability of essential antimicrobials. The current market-driven paradigm is fundamentally incompatible with public health objectives. Legislative intervention, coupled with strategic public investment, is not merely advisable-it is ethically obligatory.

Crystel Ann

January 28, 2026 AT 00:49My grandma died because they didn’t have the right antibiotic. I don’t know why this is still happening. It’s just… wrong.