Every year, thousands of older adults with dementia are given antipsychotic drugs to calm agitation, aggression, or hallucinations. It seems like a quick fix-until a stroke happens. Or worse, until they don’t wake up. The truth is, these medications are not safe for most seniors with dementia, and the risks are far worse than many families realize. Even a few weeks on these drugs can raise the chance of stroke by 80%. And yet, they’re still prescribed regularly-in nursing homes, in homes, even in hospitals-because there’s often no better plan in place.

Why Are Antipsychotics Even Used?

Dementia doesn’t just cause memory loss. It can make people confused, fearful, angry, or paranoid. They might yell, hit, pace all night, or refuse to eat. Families and caregivers are exhausted. Doctors, under pressure, sometimes reach for antipsychotics like risperidone, quetiapine, or haloperidol because they work-fast. But they don’t fix the problem. They just mute the symptoms. And the cost? A sharp rise in stroke risk, heart failure, and sudden death.

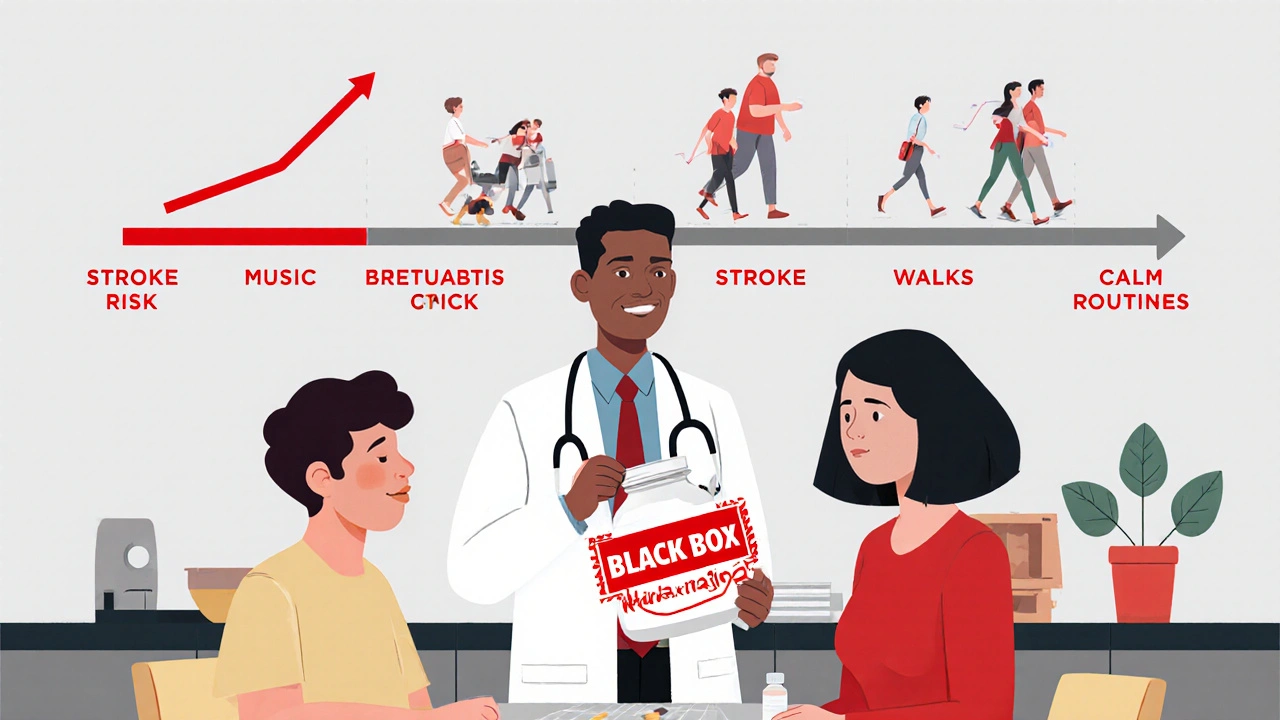

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) put a black box warning on all antipsychotics in 2005. That’s the strongest warning they can give. It says clearly: elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis have a 1.6 to 1.7 times higher risk of death when taking these drugs. That’s not a small number. That’s nearly double the risk. And stroke is one of the main reasons why.

How Do Antipsychotics Cause Stroke?

It’s not just one thing. These drugs mess with your brain’s chemistry in ways that directly affect blood flow. They can cause orthostatic hypotension-that sudden drop in blood pressure when standing up. For a senior, that means dizziness, falls, and sometimes, a clot in the brain. They also trigger metabolic changes: weight gain, high blood sugar, and high cholesterol. All of these are stroke risk factors.

Studies show that even short-term use-just a few weeks-can increase stroke risk. One major study of Veterans Affairs patients found that the moment someone started an antipsychotic, their stroke risk jumped. It wasn’t about years of use. It was about exposure. The longer they stayed on the drug, the worse it got. But even brief exposure was dangerous.

And here’s the twist: it’s not just the typical antipsychotics (like haloperidol) that are risky. The newer, “atypical” ones (like olanzapine or aripiprazole) were once thought to be safer. But research shows they carry nearly the same stroke risk. Some studies even suggest that long-term use of older drugs may be slightly worse-but the difference isn’t enough to justify using either.

Typical vs. Atypical: Does It Even Matter?

Many doctors still tell families, “We’re using the newer one-it’s safer.” That’s misleading. A 2023 review of five large studies found that while some showed slightly higher stroke risk with older antipsychotics over long periods, others found no difference at all. The American Journal of Epidemiology analyzed Medicare data and found that stroke partially explains why older antipsychotics kill more people-but not all of it. Something else is going on.

Here’s what we know for sure: both types increase the risk of stroke. Both types increase the risk of death. Both types are linked to metabolic syndrome, which leads to heart disease and more strokes. The idea that one is “safer” is a myth. The real question isn’t which drug is better-it’s whether any drug is worth the risk.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just age. It’s a mix of factors. Seniors with existing heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, or a history of mini-strokes are at the highest risk. But even healthy-looking seniors aren’t safe. One study of community-dwelling veterans found that antipsychotic use raised death risk regardless of whether they had dementia or not. The presence of dementia made it worse-but the drugs were dangerous on their own.

And it’s not just nursing homes. In fact, the highest rates of antipsychotic use are in community settings, where families are desperate and doctors are rushed. A 2022 study found that over 1 in 5 nursing home residents with dementia were on these drugs-even though guidelines say they should be avoided.

What Do the Guidelines Say?

The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria-used by doctors across the U.S. and Canada-says clearly: do not use antipsychotics for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Not ever, unless it’s a last resort. The same goes for the Alzheimer’s Association, the National Institute on Aging, and the World Health Organization.

They all say the same thing: try everything else first. Non-drug approaches. Environmental changes. Routine. Music therapy. Walking. Reducing noise. Training caregivers. These aren’t just “nice ideas.” They’re proven. One study showed that when staff were trained in person-centered care, antipsychotic use dropped by 40% in six months-with no increase in behavioral problems.

But here’s the problem: most doctors don’t have the time. Most families don’t know these options exist. And most nursing homes are understaffed and underfunded. So the pill gets prescribed.

What Should Families Do?

If your loved one has dementia and is on an antipsychotic, don’t panic-but do act.

- Ask the doctor: Why is this drug being used? What specific behavior is it targeting?

- Ask: Have non-drug strategies been tried? What were they?

- Ask: What’s the plan to reduce or stop this medication? Don’t assume it’s permanent.

- Ask: What are the signs of stroke to watch for? Sudden confusion, slurred speech, weakness on one side, vision loss-call 911 immediately.

Never stop the drug cold turkey. That can cause dangerous withdrawal. But work with the doctor on a slow, careful plan to taper off. Many seniors improve once the drug is gone-less sedation, better sleep, more alertness.

The Bigger Picture

This isn’t just about one drug. It’s about how we treat older adults with dementia. We’ve turned their natural behaviors into medical problems. We’ve made pills the first answer, not the last. But dementia isn’t a disease to be silenced. It’s a condition to be understood.

There are better ways. Specialized dementia care units. Trained staff who know how to de-escalate. Sensory rooms. Animal therapy. Even simple things like playing familiar songs from their youth can reduce agitation more than any pill.

And yet, we keep prescribing. Why? Because it’s easier. Because we don’t have the systems in place to do better. But change is possible. In New Zealand, where I live, some aged care homes have cut antipsychotic use by 70% in two years-not by adding more staff, but by changing how they think about behavior. They stopped seeing it as “bad” and started seeing it as communication.

It’s time we all do the same.

Are antipsychotics ever safe for seniors with dementia?

Antipsychotics are never truly safe for seniors with dementia. Even short-term use increases stroke risk by up to 80% and raises the chance of death by 60-70%. They are only considered in rare cases-like severe aggression that threatens safety-and only after all non-drug options have failed. Even then, they should be used at the lowest dose for the shortest time possible, with close monitoring.

Do atypical antipsychotics have fewer side effects than typical ones?

No. While atypical antipsychotics were once thought to be safer, studies show they carry nearly the same stroke and death risks as older, typical ones. Some may cause more weight gain and diabetes, while others may cause more movement problems. But when it comes to stroke risk, the difference is too small to matter. Neither class is safe for dementia patients.

How long does it take for antipsychotics to increase stroke risk?

Studies show stroke risk rises within weeks-even days-of starting the medication. One large study found that the risk was already elevated after just 10 days of use. This contradicts the old belief that only long-term use was dangerous. The truth is, any exposure carries risk, and the longer the drug is taken, the higher the chance of harm.

What are the alternatives to antipsychotics for managing dementia behavior?

Many non-drug approaches work better and are safer. These include: creating a calm, predictable routine; reducing noise and clutter; using music or familiar objects to soothe; encouraging daily walks; training staff in person-centered care; and addressing pain, constipation, or infections that can trigger agitation. Studies show these methods reduce behavioral symptoms without the deadly risks of medication.

Can antipsychotics be stopped safely?

Yes-but not suddenly. Stopping abruptly can cause withdrawal symptoms like nausea, anxiety, tremors, or even rebound aggression. The key is to work with a doctor to slowly reduce the dose over weeks or months. Many seniors become calmer, more alert, and sleep better once the drug is out of their system. Always monitor for changes during tapering.

Why are antipsychotics still prescribed if they’re so dangerous?

Because there’s often no better option available. Many care homes are understaffed. Families are overwhelmed. Doctors are pressured to “do something.” Non-drug strategies require time, training, and resources that aren’t always there. But awareness is growing. More places are adopting person-centered care models-and seeing dramatic drops in antipsychotic use without worsening behavior.

JAY OKE

November 26, 2025 AT 22:52My grandma was on risperidone for six weeks after she started yelling at the TV. One day she just... didn’t get up. They said it was a stroke. No one warned us. Not once. Just ‘it’s for her peace.’

Cynthia Springer

November 27, 2025 AT 15:11I read the FDA black box warning and still didn’t believe it until my uncle died three weeks after starting quetiapine. They said it was ‘natural progression’ of dementia. But the chart showed his BP dropped 40 points in 48 hours after the first dose. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

Brittany Medley

November 28, 2025 AT 05:16As a geriatric nurse for 22 years-I’ve seen this too many times. Families beg for something to ‘make them quiet.’ We give them the pill. Then we feel guilty. The real tragedy? The non-drug options work better-music therapy, structured walks, even just holding their hand. But staff are stretched so thin, the pill is the only thing that fits in the schedule. It’s a system failure, not a medical one.

Marissa Coratti

November 28, 2025 AT 23:24It is profoundly disturbing that the medical-industrial complex continues to prioritize pharmacological intervention over holistic, human-centered care for our most vulnerable populations. The fact that antipsychotics are still routinely prescribed despite overwhelming evidence of increased mortality, stroke risk, and metabolic deterioration speaks to a systemic devaluation of elderly dignity in favor of efficiency and profit. We must demand policy reform, increased funding for dementia care training, and mandatory non-pharmacological intervention protocols before any medication is considered-this is not just medical ethics, it is moral imperative.

Rachel Whip

November 30, 2025 AT 04:11I’ve seen this in my mom’s care home. They started her on olanzapine after she kept trying to ‘go home’-she just wanted to see her old house. The staff said she was ‘combative.’ She was confused. They gave her the pill. She slept 18 hours a day. Then she had a mini-stroke. They didn’t tell us it was the drug. I found out by reading the discharge papers.

Ezequiel adrian

November 30, 2025 AT 17:34USA doctors be selling pills like candy 🤡 My cousin in Lagos got dementia, we didn’t even have antipsychotics there-just family, prayer, and cool water on the forehead. She got better. No pills. No stroke. Just love. Y’all need to chill.

Ali Miller

December 2, 2025 AT 15:38So now we’re blaming doctors because families are too lazy to care? This is why America is collapsing. You want to avoid pills? Then hire 24/7 nurses. Pay for memory care. Stop expecting the system to fix your guilt. These drugs are dangerous? Fine. But so is letting your grandma scream all night because you won’t pay for help.

Joe bailey

December 4, 2025 AT 07:01My dad was on haloperidol for 11 days. We tapered him off slowly after reading this. Within 3 weeks, he remembered my name again. He started humming his old jazz tunes. He didn’t die. He came back. This isn’t just science-it’s a miracle you can’t buy in a pharmacy.

Amanda Wong

December 4, 2025 AT 21:29Oh please. You think this is new? People have been dying on meds since the 50s. If your relative can’t handle a little sedation, maybe they shouldn’t be living alone. This isn’t medical malpractice-it’s emotional blackmail dressed up as advocacy.

Kaushik Das

December 6, 2025 AT 04:32In India, we call dementia 'buddhi ka bhaag'-the mind’s share. We don’t label it as a disease to be crushed. We adjust the house, play old songs, feed them their favorite curry. No pills. No fear. Just patience. Maybe we’re not ‘advanced’ by Western standards-but we’re not killing them with prescriptions either.

Asia Roveda

December 6, 2025 AT 14:28Stop pretending this is about ethics. It’s about money. Pharma makes billions. Nursing homes get reimbursed for prescribing. Doctors get paid for quick visits. Non-drug care? No CPT code. No profit. Wake up. This isn’t negligence-it’s capitalism.

Micaela Yarman

December 8, 2025 AT 07:11As someone raised in a multigenerational household in Mexico, I’ve watched elders with dementia be cared for with rituals: daily walks at sunset, whispered stories, shared meals. No drugs. No restraints. Just presence. We didn’t need FDA warnings-we had love. And yet, we’re told our way is ‘backward.’ Maybe the backwardness is in thinking medicine can fix what community forgot how to do.

mohit passi

December 9, 2025 AT 09:25