Weight Loss Impact Calculator

Research shows that losing 5-10% of your body weight can lower joint load by up to 40%, reducing stress on your joints and potentially slowing osteoarthritis progression. This calculator helps you understand the potential impact of weight loss on your joint health.

How Weight Loss Helps Your Joints

Every pound lost reduces up to 4x the stress on your knees. This calculator shows how weight reduction can protect your joints from further osteoarthritis damage while also improving bone health. Research shows that losing just 5-10% of your body weight can:

- Reduce joint stress by up to 40%

- Improve joint function and mobility

- Slow the progression of osteoarthritis

- Improve bone turnover markers

When you hear the word osteoarthritis is a chronic joint disease that wears down cartilage and reshapes the underlying bone, you probably picture aching knees or stiff fingers. What many people don’t realize is that the disease reaches deep into the skeleton, changing the very fabric of bone itself. This article unpacks how osteoarthritis and overall bone health intertwine, why those changes matter, and what you can do today to protect both your joints and your skeleton.

Why the Link Matters

Bone isn’t a static scaffold; it constantly remodels in response to stress. In osteoarthritis, the remodeling process goes off‑track, leading to denser yet more brittle subchondral bone beneath the cartilage. That shift can accelerate joint degeneration and even raise the risk of fractures in other parts of the skeleton. Understanding the biology helps you make smarter lifestyle choices and discuss targeted treatments with your clinician.

What Happens to Bone Inside an OA Joint?

At the heart of the problem is the Subchondral bone is the layer of bone just below the cartilage that absorbs shock and distributes load across the joint. In a healthy joint, this bone stays porous enough to flex under pressure. In osteoarthritis, repeated stress and inflammation cause the subchondral bone to become thicker and less porous-a process called sclerosis. The thicker bone loses its shock‑absorbing ability, pushing more force onto the overlying cartilage and speeding up its erosion.

Cartilage‑Bone Crosstalk: A Two‑Way Street

Cartilage and bone talk to each other through biochemical signals. When cartilage breaks down, fragments spill into the joint space, triggering inflammatory pathways that also affect the subchondral bone. Conversely, altered bone releases cytokines that further degrade cartilage. This vicious cycle means that protecting one tissue often benefits the other.

Shared Risk Factors: Age, Weight, and Nutrition

- Age: Both osteoarthritis and bone loss increase after the fifth decade as the balance between bone formation and resorption shifts.

- Body Mass Index (BMI): Higher BMI adds mechanical load on weight‑bearing joints and releases adipokines that promote inflammation, worsening bone quality.

- Vitamin D and Calcium: Deficiencies compromise bone mineralization and may heighten inflammatory activity in joints.

Addressing these risk factors can blunt the progression of both conditions.

Distinguishing Osteoarthritis from Osteoporosis

While osteoarthritis hardens bone in specific joints, osteoporosis thins bone throughout the skeleton, making it more fracture‑prone. They can coexist, creating a paradox where a knee joint feels stiff and bony, yet the hip or spine is fragile. A simple bone density scan (DXA) can reveal osteoporosis even when osteoarthritis dominates the clinical picture.

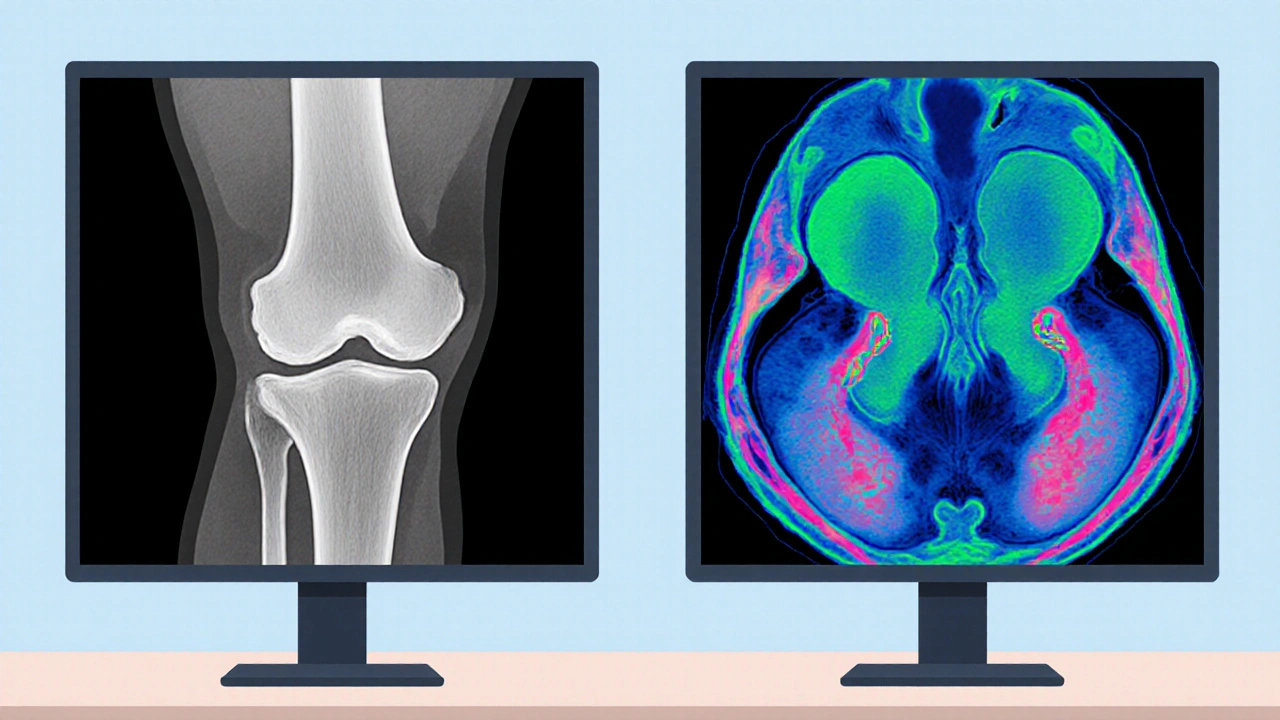

Diagnostic Tools that Reveal Bone Changes

| Modality | What It Shows | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plain Radiography | Joint space narrowing, osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis | Widely available, low cost | Limited to bone, poor soft‑tissue detail |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Bone marrow lesions, cartilage integrity, early bone edema | Detects early changes before they appear on X‑ray | Higher cost, limited availability |

| Dual‑energy X‑ray Absorptiometry (DXA) | Whole‑body bone mineral density | Gold standard for osteoporosis screening | Doesn’t assess joint‑specific bone changes |

| Quantitative Computed Tomography (QCT) | Three‑dimensional bone architecture, trabecular density | Precise measurement of subchondral bone | Higher radiation dose |

Choosing the right tool depends on whether you’re tracking joint degeneration, overall bone density, or both.

Therapeutic Strategies that Target Both Joint and Bone

- Weight Management: Losing 5-10% of body weight can lower joint load by up to 40% and improve bone turnover markers.

- Exercise: Low‑impact activities (swimming, cycling) strengthen muscles that protect joints, while resistance training stimulates bone formation.

- Nutrition: Adequate calcium (1,000mg/day) and vitamin D (800-1,000IU/day) support mineralization; omega‑3 fatty acids may dampen inflammation.

- Pharmacologic Options: NSAIDs relieve pain but don’t affect bone. Some disease‑modifying osteoarthritis drugs (DMOADs) in trials aim to restore subchondral bone quality. Bisphosphonates, used for osteoporosis, have shown mixed results in slowing joint space loss.

- Physical Therapy: Tailored programs improve joint alignment, reduce abnormal loading, and can indirectly benefit bone health.

Combining these approaches offers the best chance to keep both cartilage and bone in shape.

Lifestyle Tweaks for Everyday Bone Protection

- Stand up and move every hour-prolonged sitting reduces mechanical stimuli needed for bone remodeling.

- Incorporate strength‑training sessions at least twice a week; squats, lunges, and deadlifts are joint‑friendly when performed with proper form.

- Limit high‑impact sports if you already have joint pain; opt for water‑based aerobics instead.

- Quit smoking; nicotine interferes with calcium absorption and promotes inflammation.

- Limit alcohol to ≤2 drinks per day; excessive intake hampers bone formation.

Small daily habits stack up to big long‑term benefits.

Emerging Research: Bridging the Gap Between OA and Bone Health

Scientists are now looking at the genetic overlap between osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. Recent genome‑wide association studies (GWAS) identified shared variants in the WNT signaling pathway, a crucial regulator of bone formation. Therapies that modulate WNT activity could, in theory, treat both conditions simultaneously. Another hot area is the use of biomarkers like serum CTX‑I (a bone resorption marker) to predict rapid OA progression.

Key Takeaways

- Osteoarthritis reshapes subchondral bone, making it denser but less shock‑absorbing.

- Age, BMI, and nutrient deficiencies drive both joint degeneration and overall bone loss.

- Bone‑focused imaging (MRI, QCT) reveals early changes that plain X‑rays miss.

- Weight control, resistance exercise, and adequate calcium‑vitaminD intake protect both cartilage and bone.

- Future drugs targeting shared pathways may finally address the bone‑joint connection.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can osteoarthritis lead to osteoporosis?

Osteoarthritis itself doesn’t cause osteoporosis, but the two often coexist. Joint pain can limit physical activity, which in turn reduces the mechanical loading needed for healthy bone density, potentially accelerating osteoporosis.

Is a DXA scan enough to assess bone health in an OA patient?

A DXA scan measures overall bone mineral density and is essential for diagnosing osteoporosis, but it won’t show the localized subchondral changes typical of osteoarthritis. For joint‑specific insight, MRI or QCT is more informative.

Do supplements like glucosamine help bone health?

Glucosamine may modestly alleviate joint pain for some people, but evidence linking it to improved bone density is weak. Prioritizing calcium, vitaminD, and omega‑3 fatty acids has stronger support for bone health.

How much exercise is safe for someone with knee osteoarthritis?

Low‑impact cardio (e.g., walking, cycling) for 150 minutes per week combined with twice‑weekly resistance training is generally safe. Always start with short sessions, monitor pain, and consult a physical therapist for personalized guidance.

Are there any medications that treat both OA and bone loss?

Currently, no single drug is approved for both conditions. However, some investigators are testing WNT pathway modulators and selective bisphosphonates that might protect subchondral bone while treating osteoporosis. Stay updated with clinical trial results.

Malia Rivera

October 17, 2025 AT 17:41The bones we inherit are not just scaffolding; they are a testament to the rugged spirit of our nation. When osteoarthritis stiffens a joint, it’s like a silent rebellion against the very ground that built our country. You can fight back with weight control and strong vitamin D, just as our forebears fought for freedom. But don’t expect miracles-some damage is inevitable. In the end, a disciplined lifestyle reflects the same perseverance that shaped our history.

lisa howard

October 31, 2025 AT 00:08Oh, the drama of a knee that creaks louder than a theater curtain in a thunderstorm! You read about subchondral sclerosis and suddenly imagine bones turning into granite monuments, unfeeling and unyielding. Yet, the real tragedy is not the mineral density but the lost chorus of movement, the sighs of a joint that once sang with youthful vigor. The article mentions weight management, and I can’t help but envision a scale that judges you like a ruthless monarch, demanding a 5‑10% loss as tribute for mercy. Resistance training is touted, but who has the time to lift the weight of destiny while the world spins? Nutrition, they say, is the silent hero, yet many of us drown in fast‑food fare and forget the calcium‑rich promise of dairy. The WNT signaling pathways sound like a sci‑fi plot, but they’re the very threads weaving bone and cartilage together, a tapestry we ignore while scrolling. Imagine a future where a single pill could rewrite the genetic script, erasing the twin curses of OA and osteoporosis-sounds like a miracle, yet science edges ever nearer. MRI and QCT are lauded as crystal balls, peering into the bone’s secret chambers, but insurance companies treat them like luxury vacations. And let’s not overlook the emotional toll: the anxiety of a looming fracture, the shame of limping down a grocery aisle. The piece ends with a hopeful list of lifestyle tweaks, but hope can feel hollow when your joints protest every stair. Still, I cling to the notion that small, consistent actions-standing up every hour, a splash of omega‑3, a brisk walk-might just be the rebellion our skeleton needs. In this saga, the hero isn’t a surgeon but the everyday person who refuses to let bone become a tombstone. So, dear reader, keep moving, keep learning, and maybe, just maybe, your bones will thank you with a whisper rather than a crack.

Cindy Thomas

November 13, 2025 AT 07:34Honestly, most people think OA is just "old‑people knees," but the science shows it reshapes the entire subchondral architecture. While the article lists magnesium for bone health, it glosses over the fact that excess calcium without proper magnesium can actually worsen calcification. :) The inflammation cascade isn’t just a side effect-it’s the engine driving sclerosis. If you’re chugging down glucosamine hoping for bone density gains, you’ll be disappointed; the data just doesn’t support that claim. In fact, vitamin K2 has been shown to redirect calcium to the skeleton where it belongs. So the take‑away? Focus on the nutrients that truly matter, and don’t be fooled by trendy supplements.

Kate Marr

November 26, 2025 AT 15:01When you read about the link between osteoarthritis and bone health, remember it’s a matter of national pride to keep our bodies strong. 🇺🇸 Strong bones reflect a strong country, and the data on weight‑bearing exercise makes that crystal clear. 🏋️♀️ The article’s advice on low‑impact cardio is spot on-swap the treadmill for a swim and you protect both cartilage and bone. And yes, the vitamin D tip isn’t just a suggestion; it’s practically a civic duty. 🌞

James Falcone

December 9, 2025 AT 22:28Look, OA isn’t a death sentence and you don’t need a PhD to get the basics. Drop a few pounds, keep moving, and make sure you get enough sunshine. The article got the core right-weight loss cuts joint load big time. Also, don’t ignore that good old‑fashioned strength work actually tells bone to build up. Simple, no‑nonsense, just like we like it.

Frank Diaz

December 23, 2025 AT 05:54One could argue that the human skeleton is a philosophical metaphor, a balance of form and function, now disrupted by osteoarthritis. The subchondral sclerosis described mirrors a society that hardens its core at the expense of flexibility. Yet the remedy lies in disciplined habits-weight control, resistance training, proper micronutrients-mirroring the virtues of self‑governance. The article’s mention of WNT pathways hints at deeper cellular dialogues we scarcely comprehend. While many chase quick fixes, true wisdom resides in consistent, measured lifestyle choices. In short, bones demand respect, not shortcuts.

Mary Davies

January 5, 2026 AT 13:21The drama of a joint that once sang and now stumbles is something I feel deeply, even as I watch from the sidelines. Yet I won’t shout at the pain; I’ll simply adjust my steps and keep moving, gently. Knowing that weight‑bearing exercise can reinforce bone gives me hope without demanding sacrifice. The article’s tip on standing every hour feels like a quiet hymn to daily care. So I’ll breathe, stretch, and let my skeleton whisper thank you.

Valerie Vanderghote

January 18, 2026 AT 20:48Let me take you on a winding journey through the labyrinth of bone and cartilage, a tale as tangled as the wires behind your TV remote. First, imagine the subchondral plate as a humble foundation, once porous and forgiving, now turning into a brick wall under the relentless pressure of everyday steps. That transformation isn’t just a simple thickening; it’s a cascade of cellular whispers, a chorus of osteoblasts and osteoclasts arguing over who gets to lay down mineral today. As the article points out, the loss of shock‑absorption forces the overlying cartilage to bear the brunt, much like a tired floorboard groaning under a heavy piano. Meanwhile, inflammation spews cytokines like gossip at a family reunion, spreading from cartilage debris to bone and back again, creating a vicious loop that feels almost inevitable. The risk factors-age, BMI, vitamin D-are the familiar villains in this saga, each adding a layer of complexity to the plot. Yet there’s a silver lining: weight management isn’t just dieting; it’s a strategic retreat, a tactical withdrawal that reduces joint load by up to 40 %, buying precious time for the skeleton. Exercise, especially low‑impact activities, act like gentle sculptors, coaxing bones to remodel without breaking them. The article’s emphasis on nutrition deserves a standing ovation; calcium and vitamin D are the building blocks, while omega‑3s act as peacekeepers, calming the inflammatory battlefield. Imaging modalities such as MRI and QCT are the investigative journalists of the medical world, exposing hidden bone marrow lesions before they become headline news. And let’s not forget emerging research-WNT signaling isn’t just a fancy term; it’s a potential master key that could unlock therapies addressing both OA and osteoporosis simultaneously. In the grand theater of health, the bone‑joint duo takes center stage, and we, the audience, must decide whether to sit back or take an active role in the performance. So, dear reader, march on with resistance bands, savor your leafy greens, and remember that every small habit is a brushstroke on the canvas of your skeletal masterpiece.

Emily (Emma) Majerus

February 1, 2026 AT 04:14lose a lil weight and ur bones thank u.

Virginia Dominguez Gonzales

February 14, 2026 AT 11:41Great job pulling out those practical tips! I love how you highlighted the power of simple daily moves-standing up, a quick stretch, a short walk. It’s exactly the kind of encouragement we need to keep our skeletons happy. Keep spreading the positivity!