When you’re dealing with autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or alopecia areata, finding a treatment that works without daily injections can feel like a breakthrough. That’s where JAK inhibitors come in. These oral drugs have changed how millions manage chronic inflammation - but they’re not without risks. If you’ve been prescribed one, or are considering it, you need to understand not just how they work, but what you must watch for.

How JAK Inhibitors Actually Work

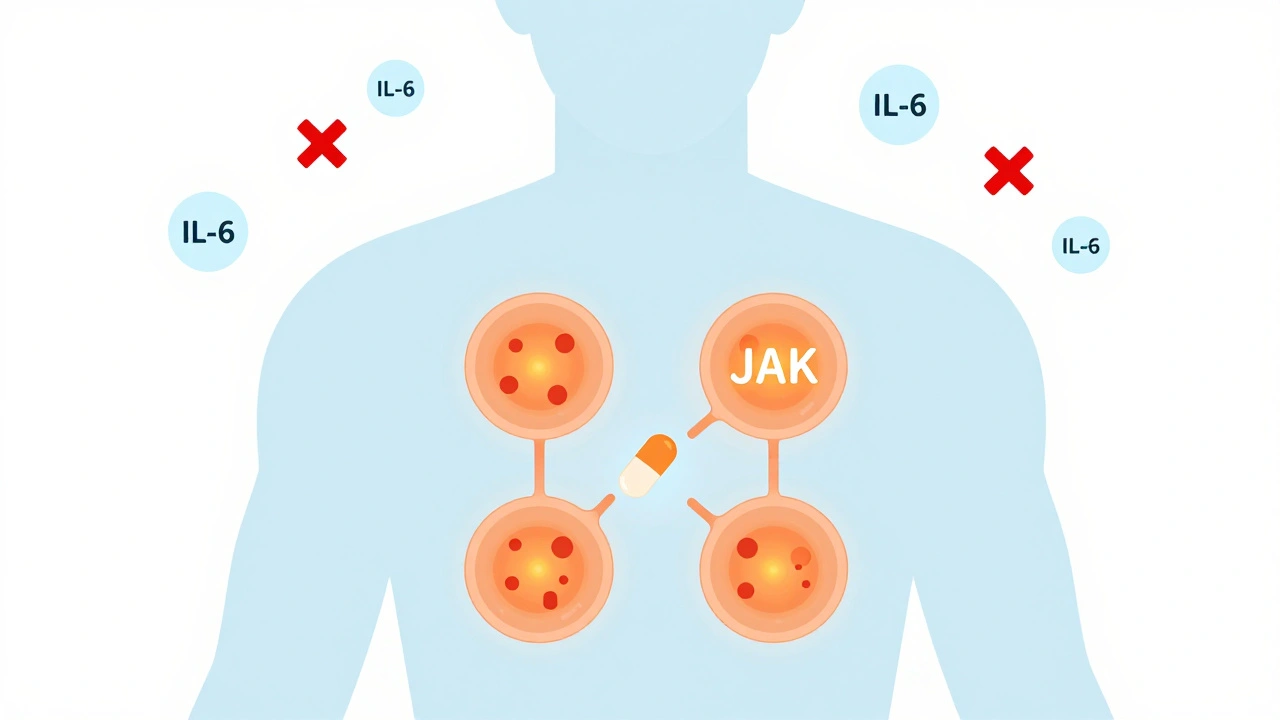

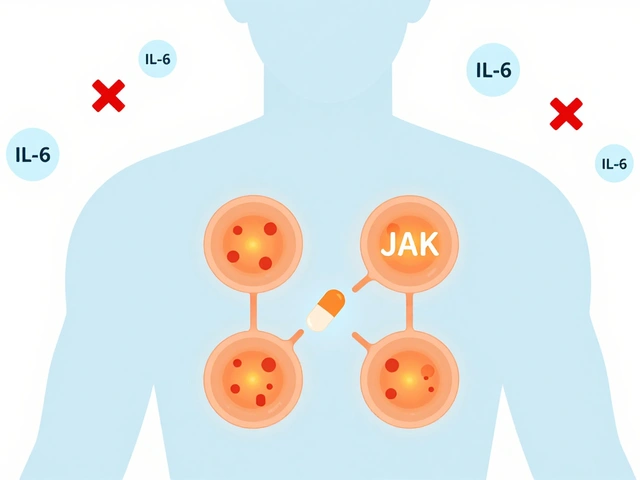

JAK inhibitors don’t target single proteins like older biologics do. Instead, they block the inside of immune cells - specifically, the Janus Kinase (JAK) enzymes that act like switches for inflammation signals. These enzymes sit near receptors on cell surfaces. When cytokines like IL-6 or interferon attach, JAKs get activated and turn on genes that cause swelling, pain, and tissue damage. JAK inhibitors slip into the enzyme’s active site, stopping the signal before it even starts.

There are four types of JAK enzymes: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2. Different drugs hit different combinations. For example, upadacitinib is highly selective for JAK1, which helps control inflammation while reducing side effects tied to JAK2 (like anemia or low platelets). Abrocitinib targets JAK1 and JAK2, making it powerful for skin conditions like atopic dermatitis. Ritlecitinib works differently - it binds permanently to JAK3, a move that could mean longer-lasting effects with lower doses.

This broad action is why one pill can help with multiple problems. Someone with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis might see both improve at the same time. But it’s also why side effects can be tricky - you’re turning down the volume on more than just the bad signals.

Why They’re Popular - And Why They’re Controversial

Since tofacitinib became the first FDA-approved JAK inhibitor in 2012, these drugs have exploded in use. They’re taken as pills. You don’t need a clinic visit every few weeks for an infusion. Patients report symptom relief in as little as two weeks - faster than most biologics. A 2023 survey of over 1,200 users found 92% preferred taking a pill over injections. For many, that convenience alone makes the difference.

But the same mechanism that makes them effective also makes them risky. In 2022, the FDA added a black box warning - the strongest possible - to all JAK inhibitors. The warning highlights four serious dangers: major cardiovascular events (like heart attacks or strokes), blood clots, cancer, and life-threatening infections.

The ORAL Surveillance trial, which followed over 4,000 rheumatoid arthritis patients over eight years, found that those on tofacitinib had a 31% higher risk of major heart problems and a 49% higher risk of cancer compared to those on TNF inhibitors. That’s not a small difference. It’s why guidelines now say JAK inhibitors shouldn’t be used in patients over 65 with heart disease, smokers, or anyone with a history of cancer.

Who Should and Shouldn’t Take Them

Not everyone is a candidate. The American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism agree: JAK inhibitors are second-line. Use them after methotrexate fails, and after trying a TNF inhibitor - unless you can’t tolerate injections or need faster results.

They’re best for people who:

- Have moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or alopecia areata

- Have no history of blood clots, heart disease, or cancer

- Are under 65

- Don’t smoke

- Have normal blood counts and liver function

Avoid them if you:

- Have had a recent heart attack or stroke

- Have active tuberculosis or hepatitis B

- Have low white blood cell counts

- Are pregnant or planning to be

Even if you’re healthy now, your risk changes over time. That’s why monitoring isn’t optional - it’s essential.

What You Must Monitor - And How Often

Starting a JAK inhibitor isn’t like starting a blood pressure pill. You need regular blood tests. The American College of Rheumatology says:

- Before starting: Complete blood count, liver enzymes, lipid panel, TB test, and hepatitis screening.

- First 3 months: Every 4 weeks.

- After 3 months: Every 3 months for the first year, then every 6 months.

Here’s what they’re looking for:

- White blood cells: If your absolute lymphocyte count drops below 500 cells/μL, stop the drug. This means your immune system is too suppressed.

- Hemoglobin: Below 8 g/dL? That’s severe anemia. It can happen with JAK2 inhibition.

- Liver enzymes: ALT or AST more than three times the normal level? Pause treatment and investigate.

- Cholesterol: LDL cholesterol often rises by 20-30 mg/dL. If it hits 190 mg/dL or higher, start a statin. This isn’t just about heart health - high cholesterol is a known risk factor for cardiovascular events with these drugs.

Also, herpes zoster (shingles) is a big concern. About 23% of users report reactivation. That’s 7 times higher than with biologics. Many doctors now prescribe antivirals like valacyclovir as a preventive, especially if you’ve had shingles before.

And don’t forget vaccines. The European Medicines Agency recommends getting the shingles vaccine at least 4 weeks before starting. But in real-world clinics, only about 32% of patients do. Too many are rushed into treatment because their symptoms are bad - and that’s dangerous.

Real Stories - The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

One Reddit user, u/RhuemWarrior, wrote in June 2024: “Abrocitinib cleared my eczema in 10 days - but gave me shingles twice. Now I’m on daily antivirals and terrified of what’s next.”

Another, on HealthUnlocked, shared: “After failing three biologics, baricitinib dropped my swollen joints from 18 to 2 in six weeks. The $15 co-pay increase? Worth it.”

These aren’t outliers. They’re the reality. JAK inhibitors can be life-changing - or life-threatening. The difference often comes down to monitoring. The patient who gets blood tests every 3 months catches a rising cholesterol or falling lymphocyte count before it becomes a crisis. The one who skips tests? They might not know something’s wrong until they’re in the ER.

What’s Next? New Drugs, Better Safety

The field is moving fast. Deuruxolitinib got FDA approval for alopecia areata in June 2024 - with a mandatory risk management program. Brepocitinib, a new TYK2 inhibitor, is in phase 3 trials and expected to launch in 2025. Unlike older JAK inhibitors, it targets only one enzyme, potentially cutting side effects.

Also, JAK3 inhibitors with covalent binding (like ritlecitinib) are designed to stick to their target longer, meaning lower doses and fewer off-target effects. Early data looks promising.

But even these newer drugs won’t eliminate risk. The 2024 follow-up to the ORAL Surveillance trial confirmed: the cancer risk with tofacitinib remains elevated even after 8.5 years. That’s not going away. The goal now isn’t to make JAK inhibitors safer - it’s to use them smarter.

Bottom Line: Powerful, But Not for Everyone

JAK inhibitors are powerful tools. They’re fast, convenient, and effective for many. But they’re not magic. They carry real, documented risks that don’t go away with time. If you’re on one, don’t skip your blood tests. Talk to your doctor about your heart health, your smoking status, your vaccine history. If you’re considering one, ask: “Am I the right patient for this?”

For the right person, it can mean relief from pain, clearer skin, and hair regrowth. For the wrong person, it could mean a heart attack, cancer, or a life spent on antivirals. The choice isn’t just about effectiveness - it’s about vigilance.

Are JAK inhibitors safe for long-term use?

Long-term safety data shows increased risks of serious infections, cancer, and heart problems, especially after 5+ years. The ORAL Surveillance trial found a 49% higher risk of cancer and 31% higher risk of major cardiovascular events compared to TNF inhibitors. These risks don’t disappear over time, so ongoing monitoring and careful patient selection are critical. They’re not recommended for people over 65, smokers, or those with a history of cancer or blood clots.

How often do I need blood tests while on a JAK inhibitor?

You need blood tests every 4 weeks for the first 3 months, then every 3 months for the first year, and every 6 months after that. Tests include complete blood count, liver enzymes, cholesterol levels, and kidney function. Skipping tests increases your risk of undetected anemia, low white blood cells, or liver damage - all of which can become serious without warning.

Can I get vaccinated while taking a JAK inhibitor?

Yes - but timing matters. Live vaccines (like shingles or MMR) should be given at least 4 weeks before starting the drug. Inactivated vaccines (flu, COVID, pneumonia) are safe to take while on treatment. Many patients miss the pre-treatment window because symptoms are urgent, but that increases their risk of shingles. Always check with your doctor before any vaccine.

Do JAK inhibitors cause weight gain or hair loss?

Weight gain isn’t a direct side effect, but some patients gain weight due to improved appetite after inflammation is controlled. Hair loss isn’t caused by JAK inhibitors - in fact, they’re used to treat it. Drugs like ritlecitinib and deuruxolitinib are FDA-approved for alopecia areata and can regrow hair in many patients. If you’re losing hair while on one, it’s likely unrelated and should be evaluated.

What’s the difference between JAK inhibitors and biologics like Humira?

Biologics like Humira (adalimumab) target specific proteins outside cells, such as TNF-alpha. JAK inhibitors work inside cells to block signals from multiple cytokines at once. That’s why JAK inhibitors work faster - often in 2 weeks versus 8-12 for biologics - and can treat multiple conditions at once. But because they’re less targeted, they carry more systemic risks. Biologics are safer for older patients with heart disease; JAK inhibitors are not.

Can I stop taking a JAK inhibitor if I feel better?

Don’t stop without talking to your doctor. Stopping suddenly can cause a flare-up of your disease - sometimes worse than before. Some patients can taper under supervision, especially if they’ve been in remission for over a year. But many will need to stay on it long-term. The decision should be based on your disease activity, test results, and risk profile - not just how you feel.

Irving Steinberg

December 2, 2025 AT 20:53Kay Lam

December 4, 2025 AT 11:32Michelle Smyth

December 5, 2025 AT 11:05Conor Forde

December 5, 2025 AT 14:03Declan Flynn Fitness

December 5, 2025 AT 19:13Priyam Tomar

December 7, 2025 AT 19:03Adrian Barnes

December 9, 2025 AT 04:33Walker Alvey

December 10, 2025 AT 14:08patrick sui

December 11, 2025 AT 00:38Lydia Zhang

December 12, 2025 AT 04:42Patrick Smyth

December 12, 2025 AT 07:42Linda Migdal

December 13, 2025 AT 15:45Declan O Reilly

December 13, 2025 AT 21:39Adrian Barnes

December 15, 2025 AT 13:55Tommy Walton

December 17, 2025 AT 04:12