Every year, millions of people turn to opioids for pain relief-after surgery, injury, or chronic conditions. But for every person who finds relief, others face a dangerous path toward dependence, overdose, or worse. In 2025, over 108,000 Americans died from drug overdoses, and synthetic opioids like fentanyl were behind 86% of those deaths. The good news? We now have clearer, science-backed ways to manage pain without putting lives at risk. The key isn’t banning opioids-it’s using them smarter.

When Opioids Are Necessary-and When They’re Not

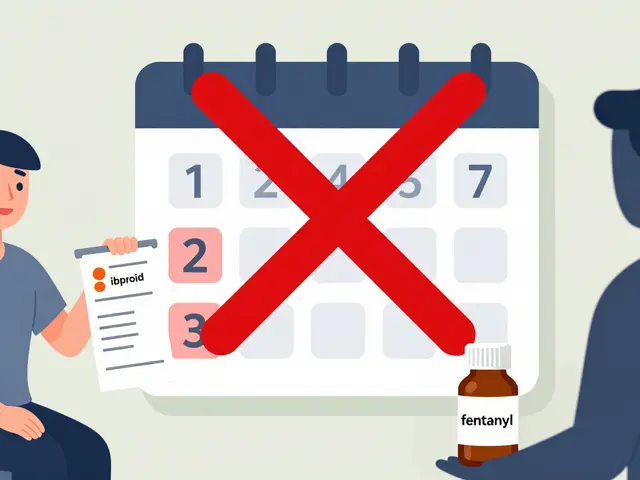

Opioids aren’t evil. They’re powerful tools. But they’re like a chainsaw: useful in the right hands, dangerous in the wrong ones. The 2025 CDC guidelines make this clear: for most acute pain-like after a dental extraction or a sprained ankle-a three-day supply is enough. That’s it. Studies show that each extra day beyond three increases the chance of long-term use by 20%. Many patients don’t even finish their three-day prescription. Yet for years, seven-day scripts were the norm. That’s changing.For chronic pain, the story gets more complex. If you’ve been on opioids for years and are stable, you may still need them. But the rules around those prescriptions have tightened. Doses above 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day come with a warning: your risk of overdose jumps nearly threefold. At 90 MME or higher, the risk becomes so high that most experts agree it should only be used in rare cases-like active cancer or end-of-life care.

Here’s the reality: most people don’t need opioids at all. For back pain, arthritis, or headaches, NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen work just as well-with fewer risks. Acetaminophen, physical therapy, nerve blocks, and even cognitive behavioral therapy can reduce pain without touching opioids. The American Academy of Pain Medicine and the International Association for the Study of Pain both say the same thing: opioids should be the last resort, not the first.

The New Rules: What Doctors Must Do in 2026

Since January 2025, every pharmacy in the U.S. has been required to run safety checks before filling an opioid prescription. This isn’t optional. It’s built into the system. If a patient is being prescribed opioids for the first time for acute pain, the system will block a prescription longer than three days unless the doctor manually overrides it-and they have to document why.For patients already on opioids, the system flags anything above 90 MME per day. That doesn’t mean the prescription is denied-it means the pharmacist must contact the prescriber. This is designed to catch cases where someone’s dose has crept up over time without proper review.

Doctors are also now required to check the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) before writing any opioid script. This database shows if a patient is getting opioids from multiple doctors. Studies show checking the PDMP cuts overlapping prescriptions by 37%. That’s a big deal. One patient I know was getting oxycodone from three different providers. He didn’t even realize it. The PDMP caught it before he overdosed.

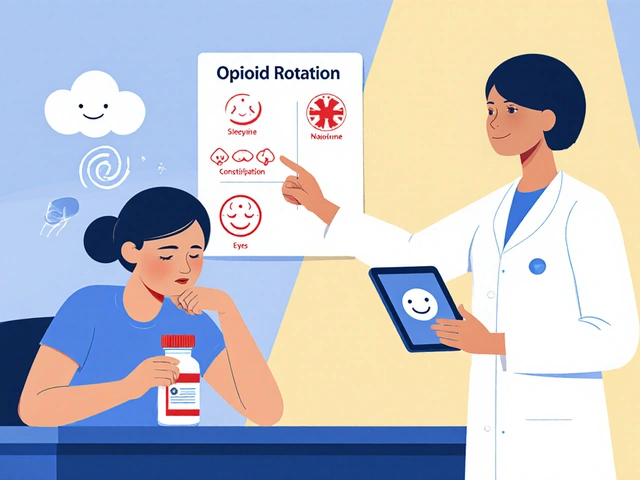

Documentation has also gotten stricter. If you’re on 50 MME or more, your doctor needs to note your pain levels, your functional status, your mental health, your family history of addiction, and your plan for reducing opioids if things don’t improve. That might sound like bureaucracy, but it’s meant to stop the drift-where someone quietly gets higher doses because no one ever asked, "Is this still helping?"

What Happens When You Taper Too Fast

Here’s one of the most misunderstood parts of opioid safety: stopping opioids suddenly can be deadly. In 2024, a major study found that patients whose opioids were rapidly cut off had a 23% increase in suicide attempts. That’s not a coincidence. For people with chronic pain, opioids can become part of their daily stability. Taking them away without a plan can trigger severe withdrawal, unbearable pain, depression, and hopelessness.The FDA updated its labeling in July 2025 to make this crystal clear: "Rapidly reducing or abruptly discontinuing opioids may result in serious withdrawal symptoms, uncontrolled pain, and suicide." That’s not a footnote. It’s in bold. Doctors who taper too fast aren’t helping-they’re risking lives.

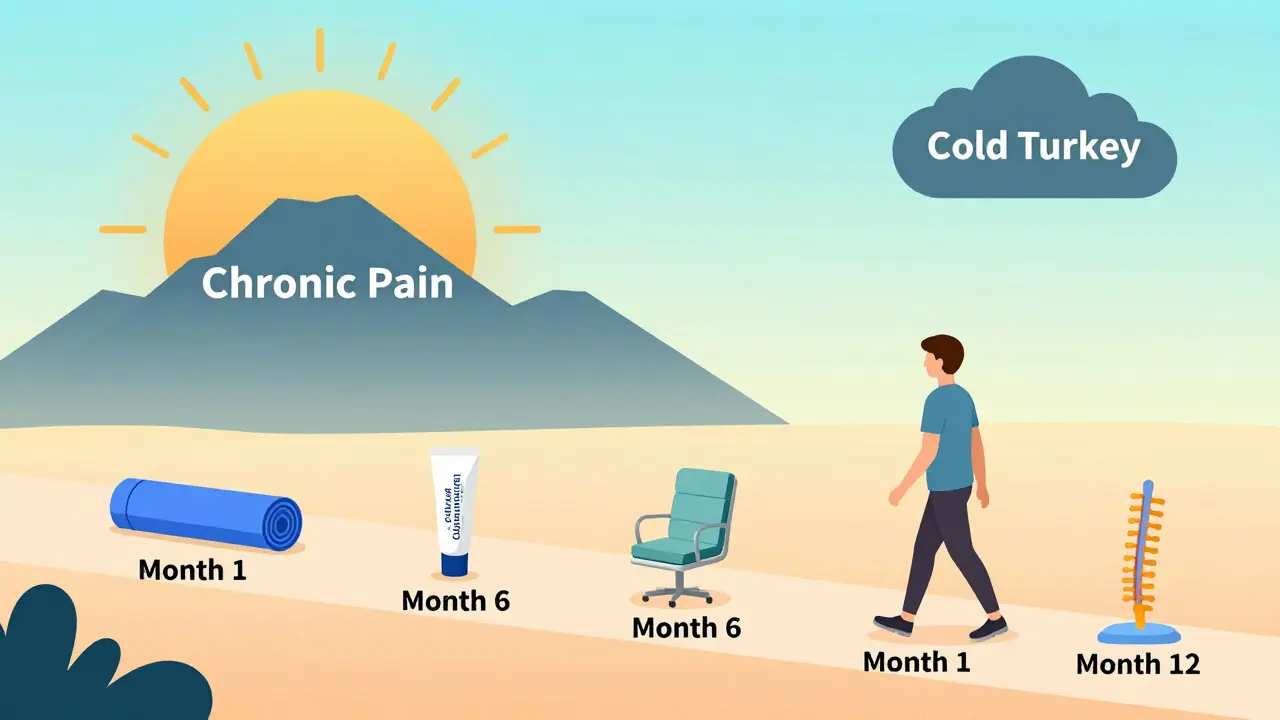

The right way to taper? Slow. Personalized. Supported. If you’ve been on 80 MME for five years, dropping to zero in a month isn’t safety-it’s neglect. A safe taper might take months or even a year. It’s paired with non-opioid pain tools: physical therapy, mindfulness, nerve stimulation, or even low-dose antidepressants that help with nerve pain. And it’s done with someone you trust.

Alternatives That Actually Work

The biggest shift in pain management isn’t about opioids-it’s about what comes before them. Non-opioid options are growing fast. In 2024, the pain management market was worth $34.7 billion. By 2030, it’s expected to grow over 5% annually, mostly because of non-opioid drugs and therapies.NSAIDs like celecoxib and naproxen are still first-line for arthritis and muscle pain. Acetaminophen works well for mild to moderate pain and is safe for most people when used correctly. Topical creams with lidocaine or capsaicin can relieve localized pain without affecting the whole body.

Then there are the non-drug options. Physical therapy isn’t just stretching-it’s movement retraining, strength building, and pain education. For lower back pain, studies show physical therapy is just as effective as surgery-with no risk of addiction. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) helps rewire how the brain processes pain signals. It’s not "just in your head." It’s science.

Even newer tools are emerging. CBD-based products, while still under study, are showing promise for nerve pain and inflammation. Nerve blocks and spinal cord stimulators are helping people who’ve tried everything else. And in 2026, the NIH is pouring $125 million into developing non-addictive pain medications. The future isn’t about better opioids-it’s about replacing them.

Why Some Patients Are Falling Through the Cracks

The system is improving, but it’s not perfect. In 2025, a survey by the U.S. Pain Foundation found that 7-10% of long-term opioid users had their prescriptions cut off abruptly. Many ended up in emergency rooms with uncontrolled pain. Others turned to street drugs because they couldn’t get help.This isn’t just about doctors being harsh. It’s about broken systems. Small clinics don’t have the staff to manage complex pain cases. Rural areas lack pain specialists-68% of rural counties don’t have a single pain clinic. Surgeons, who often prescribe opioids after operations, are the least likely to follow the new guidelines. Only 43% of them use the CDC’s 2025 recommendations.

And then there’s the cost. Implementing PDMP checks, electronic alerts, staff training, and new protocols can cost a practice $18,500 on average. Many small offices can’t afford it. That’s why adoption is uneven. Primary care doctors? 82% are using the guidelines. Dentists? 67%. Surgeons? Far behind.

The result? A two-tiered system. People with good insurance, access to specialists, and supportive clinics get safe, thoughtful care. Others get rushed decisions, sudden stops, or no help at all.

What You Can Do-As a Patient or Caregiver

If you’re prescribed an opioid, ask these questions:- Is this the lowest effective dose?

- How long will I need it?

- What are the non-opioid options I haven’t tried yet?

- Will you check my state’s prescription database before writing this?

- What’s the plan if the pain doesn’t improve in a few weeks?

If you’re on opioids long-term, don’t hide your use. Talk to your doctor about your risks. Ask about urine drug screening-it’s not about distrust. It’s about safety. It helps catch other substances like alcohol or benzodiazepines that can turn an opioid into a lethal mix.

And if you’re worried about withdrawal? Don’t try to quit cold turkey. Ask for help. There are programs-like the VA’s Opioid Safety Initiative-that offer counseling, tapering plans, and alternative pain treatments. You don’t have to do this alone.

The Bigger Picture

The opioid crisis didn’t happen overnight. It was built over decades of overprescribing, weak oversight, and a healthcare system that rewarded quick fixes. But we’re learning. The CDC, FDA, and CMS have aligned on clear, evidence-based standards. States are adopting stricter limits. Pharmacies are blocking unsafe scripts. Research is pointing toward better alternatives.The goal isn’t to eliminate opioids. It’s to make sure they’re used only when truly needed-and never at the cost of someone’s life. In 2026, we have the tools. What’s missing is consistent use. Every doctor, pharmacist, and patient has a role. We can reduce overdoses by 20% or more. But only if we all act-not just with rules, but with compassion.

Shane McGriff

January 19, 2026 AT 16:47Just saw my cousin’s doctor cut her off opioids cold turkey after 8 years. She ended up in the ER with seizures. This post is spot-on-tapering isn’t optional, it’s medical ethics. The FDA warning should be plastered on every prescription bottle.

Renee Stringer

January 21, 2026 AT 07:17People who say opioids are ‘necessary’ are ignoring how easily addiction sneaks in. One prescription, one bad habit. No one wakes up wanting to die. But they do wake up needing pills. It’s not about compassion-it’s about accountability.

Crystal August

January 21, 2026 AT 08:10Why are we still talking about this? The system’s broken. Doctors don’t care. Pharmacies just follow rules. Patients suffer. And the ‘non-opioid alternatives’? Half of them cost $500 a month. Good luck on Medicaid.

Nadia Watson

January 22, 2026 AT 04:55As someone who’s navigated chronic pain for over a decade, I appreciate the nuance here. Non-opioid options like CBT and physical therapy changed my life-but only after I found a provider who actually listened. Too many clinics treat pain like a checkbox. It’s not. It’s a human experience. And yes, I’ve seen PDMP flags save lives. One doctor caught me getting oxycodone from two states. I didn’t even know I was doing it. That’s not surveillance-it’s salvation.

Courtney Carra

January 22, 2026 AT 06:41We’re treating pain like a math problem: 3 days = safe. 90 MME = danger zone. But pain isn’t linear. It’s emotional. It’s cultural. It’s the quiet sob at 3 a.m. when the meds wear off and the bills pile up. Science gives us tools-but compassion gives us humanity. And we’re losing that in the algorithm.

Thomas Varner

January 22, 2026 AT 19:28My uncle’s surgeon gave him a 30-day script after a knee replacement. He finished it in 11 days. No issues. No cravings. So why the blanket rules? Maybe the problem isn’t opioids-it’s lazy prescribing. Not every patient is a statistic.

Art Gar

January 24, 2026 AT 01:01The CDC guidelines are bureaucratic overreach. If I’m stable on 70 MME, why should a pharmacist call my doctor? Who authorized them to police my body? This isn’t safety-it’s paternalism dressed as science.

Edith Brederode

January 24, 2026 AT 17:14Just wanted to say thank you for writing this. My mom’s on a slow taper now-3 months in, and she’s sleeping through the night for the first time in years. We’re using CBD oil, acupuncture, and daily walks. It’s not perfect. But it’s better than the numbness she had before.

Arlene Mathison

January 25, 2026 AT 23:06STOP. Just stop. You don’t need opioids for back pain. Try yoga. Try chiropractic. Try not being a couch potato. People think pain is a right, not a condition to manage. Get up. Move. Stop blaming the system. Your pain isn’t special.

Emily Leigh

January 26, 2026 AT 01:02So… what’s the point? We’re all gonna die anyway. At least let people have their peace. If I wanna numb out, it’s my body. The government’s got better things to do than babysit my pain meds.

Carolyn Rose Meszaros

January 27, 2026 AT 07:57My sister’s a nurse in rural Ohio. She told me half the clinics don’t even have PDMP access. So yeah, the guidelines are great… if you live in a city with WiFi and a salary. For the rest of us? It’s still the Wild West.

Greg Robertson

January 28, 2026 AT 17:26I’ve been on 45 MME for 6 years. I’m not addicted. I’m functional. I work, I parent, I cook dinner. Why does my doctor need to document my family history of addiction? I’m not a criminal. Just let me live.

thomas wall

January 29, 2026 AT 04:33The notion that opioid reduction equates to moral superiority is not only reductive-it is dangerously misguided. The American healthcare apparatus has become a punitive machine, masquerading as benevolence. To impose rigid thresholds upon individuals whose suffering is both chronic and intractable is not reform-it is cruelty cloaked in data. The true epidemic is not opioid misuse; it is the systemic abandonment of the vulnerable under the guise of public health.