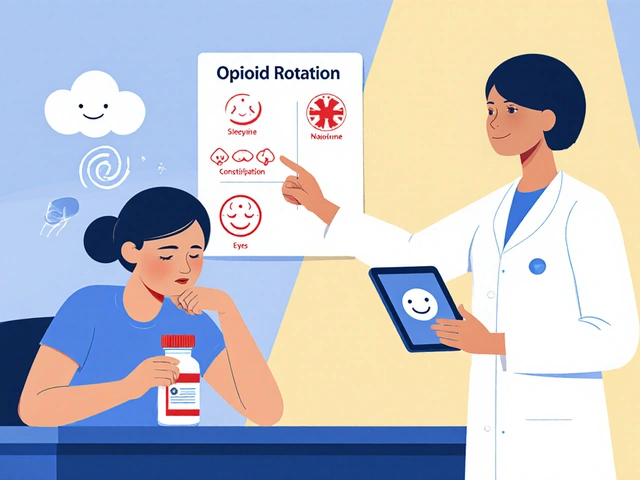

After surgery, pain is inevitable-but how you manage it can make all the difference. For years, doctors reached for opioids as the go-to solution. But the risks-addiction, nausea, drowsiness, even respiratory depression-have led to a major shift. Today, the standard isn’t just about controlling pain. It’s about controlling it without relying on opioids. That’s where multimodal analgesia (MMA) comes in.

What Is Multimodal Analgesia?

Multimodal analgesia means using more than one type of pain relief at the same time. Instead of stacking high doses of one drug, like morphine, doctors combine several lower-dose medications that work in different ways. Think of it like building a wall with different kinds of bricks. Each one adds strength, but you don’t need as many of any single type. The goal? Reduce opioid use by 30% to 60%, while keeping pain under control. Studies show this approach cuts nausea and vomiting by nearly a third, shortens hospital stays, and lowers the chance of developing long-term pain. It’s not experimental anymore. Since 2021, 14 major medical societies-including the American Society of Anesthesiologists-have agreed: MMA is the new standard for most surgeries.How It Works: The Core Medications

MMA isn’t one magic pill. It’s a smart mix of drugs that target pain at different points in the body’s signaling system.- Acetaminophen (Tylenol): Works in the brain to reduce pain signals. Given every 6 hours, even before surgery, it cuts opioid needs by up to 25%.

- NSAIDs like celecoxib and naproxen: Reduce inflammation at the surgical site. Celecoxib is often used for spine or joint surgeries; naproxen is common in trauma cases-but it’s avoided if kidney function is low (eGFR under 30).

- Gabapentin or pregabalin: These calm overactive nerves. Used before and after surgery, they help with nerve-related pain, especially after spine or amputation procedures. Dosing is adjusted for kidney health.

- Ketamine: A low-dose anesthetic that blocks pain pathways in the spinal cord. Given as a slow IV drip, it’s especially useful for high-risk patients or those with chronic pain.

- Lidocaine: An IV infusion that blocks nerve signals system-wide. Used for major surgeries like spine or abdominal procedures, it can reduce opioid use by up to 40%.

- Dexmedetomidine: A sedative that also reduces pain sensitivity. Often used during surgery and in recovery to keep patients calm without heavy opioids.

These aren’t chosen randomly. They’re picked based on the type of surgery, the patient’s health, and their pain history. For example, a knee replacement might use acetaminophen, gabapentin, and a nerve block. A spinal fusion might add ketamine and lidocaine.

Timing Matters: Before, During, and After

MMA doesn’t start when you wake up from surgery. It starts before you even go under the knife.- Preoperative: Giving acetaminophen, gabapentin, and celecoxib 1-2 hours before surgery reduces the body’s pain response from the start. This is called pre-emptive analgesia.

- Intraoperative: During surgery, anesthesiologists may add ketamine, lidocaine, or dexmedetomidine to the IV line. Regional nerve blocks-guided by ultrasound-are also used to numb the surgical area.

- Postoperative: Scheduled doses of non-opioid meds continue every few hours. Opioids? Only for breakthrough pain. A patient might get 1-2 mg of morphine every 15 minutes if needed, but only after the other meds have had time to work.

At Rush University Medical Center, this approach cut average daily opioid use from 45.2 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to just 18.7 MME-a 61% drop. Pain scores stayed below 4 out of 10.

Who Benefits Most?

MMA works best in surgeries with predictable, localized pain:- Orthopedic: Total knee or hip replacements see 50-60% less opioid use.

- Spine surgery: Multimodal protocols reduce opioid needs by 40-55%.

- Abdominal and thoracic: Especially helpful after major operations like colectomies.

It’s also critical for high-risk patients:

- Those with chronic pain

- People with a history of opioid use

- Patients with kidney or liver issues

- Those who request opioid-free surgery

For these groups, protocols include extended lidocaine infusions, longer ketamine courses, and even continuous wound catheters that drip numbing medicine directly into the surgical site for 2-3 days after surgery.

Challenges and Pitfalls

MMA isn’t simple. It requires teamwork.- Coordination: Nurses, anesthesiologists, pharmacists, and surgeons must all be on the same page. A missed dose of gabapentin before surgery can throw off the whole plan.

- Renal and liver function: Gabapentin and naproxen need dose adjustments for kidney disease. Giving naproxen to someone with eGFR under 30 can cause serious harm.

- Access to regional anesthesia: Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks are key-but not every hospital has the equipment or trained staff.

- Documentation: Pain must be tracked every 2 hours for the first 24 hours. Without data, you can’t adjust treatment.

And it’s not a one-size-fits-all. A 70-year-old with diabetes and kidney disease needs a different plan than a 30-year-old athlete. That’s why the guidelines stress individualization.

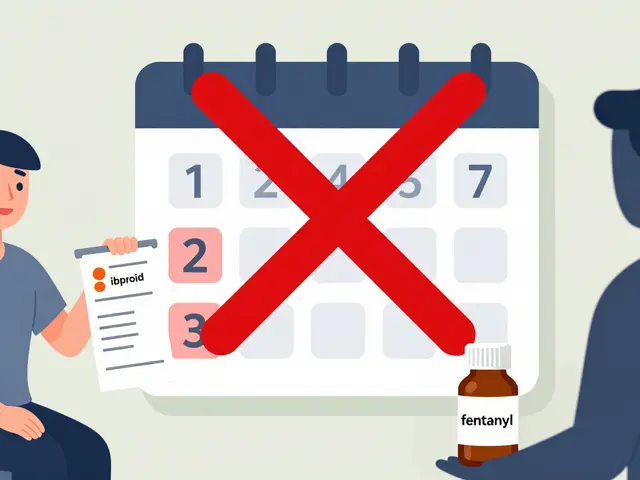

What Happens When You Go Home?

Pain doesn’t end at discharge. In fact, the first week after surgery is when many patients start using opioids long-term.New protocols now include a 5- to 10-day course of gabapentin or acetaminophen to prevent pain from becoming chronic. At McGovern Medical School, patients on their trauma pathway had a 25% higher rate of same-day discharge-and stayed out of the hospital longer because their pain was better managed at home.

Prescribing opioids after surgery? Only if non-opioid meds fail. And even then, limit it to a 5-day supply unless absolutely necessary.

The Future of Pain Control

By 2025, 85% of major surgeries are expected to use formal MMA protocols. That’s up from 60% in 2022. The push isn’t just about safety-it’s about outcomes.Reducing opioids means fewer overdoses, fewer addictions, and less chronic pain. It means patients recover faster, leave the hospital sooner, and get back to their lives.

The message is clear: opioids have a role-but only as a backup. The future of surgical pain management isn’t about stronger drugs. It’s about smarter ones.

Deepika D

January 1, 2026 AT 10:34Wow, this is such a game-changer for post-op care. I’ve seen too many patients get hooked on opioids after minor surgeries, and it’s heartbreaking. The idea of stacking non-opioid meds like acetaminophen, gabapentin, and lidocaine before the knife even touches skin? Genius. I work in a rural hospital in India where we don’t always have ultrasound machines for nerve blocks, but even just starting gabapentin pre-op and sticking to scheduled Tylenol has cut our opioid prescriptions by half. It’s not magic-it’s just smart, consistent, patient-centered care. Nurses need training, pharmacists need to be in the loop, and docs need to stop defaulting to oxycodone like it’s candy. We can do better. We’re already doing better, just not everywhere.

And honestly? Patients feel more like themselves when they’re not foggy from morphine. They can breathe, laugh, sit up, text their kids. That’s recovery. That’s dignity. Let’s keep pushing this forward-every hospital, every country, every surgeon.

Also, if you’re a patient reading this: ask for MMA. Don’t just take what’s handed to you. You deserve pain control without the haze.

PS: If your doc says ‘it’s too complicated,’ tell them to read this post and come back. I’ll wait.

PPS: Gabapentin dosing for renal impairment? Always check eGFR. Don’t wing it. I’ve seen the crashes.

PPPS: We need more global guidelines. Not just US-centric. This works in Lagos, in Manila, in Delhi. It just needs the will.

PPPPS: I’m not a doctor. I’m a nurse who’s seen too many overdoses. This saved my cousin’s life after knee surgery. Just saying.

Retha Dungga

January 1, 2026 AT 18:28So opioids are bad now 🤔 but what about the people who actually need them 😔 like my uncle who had spinal fusion and couldn’t move without 20mg oxycodone every 4 hours 🥲 maybe the system is just too rigid now 🤷♀️

Also why is everyone so scared of addiction 🤨 like we’re all gonna turn into zombies if we take one pill 🙄

But hey… if gabapentin helps… cool I guess 🤷♀️

Jenny Salmingo

January 2, 2026 AT 03:23I had knee surgery last year and they didn’t give me any opioids at all. Just Tylenol and ibuprofen. I was shocked. But honestly? I felt better. No dizziness. No nausea. I could walk to the bathroom without help. My grandma even said I looked like myself again. It’s weird how something so simple works so well. I wish more hospitals did this.

Also, gabapentin made me a little sleepy, but not in a bad way. More like cozy sleepy. Like a blanket for your nerves.

Frank SSS

January 3, 2026 AT 11:33Look, I get it. Opioids are scary. But let’s not pretend this is some revolutionary breakthrough. We’ve known about NSAIDs and gabapentin for decades. The real issue? Hospitals don’t pay nurses enough to track pain scores every two hours. And why? Because they’d rather bill for opioids than invest in staff training.

Also, ‘multimodal analgesia’ sounds fancy, but it’s just code for ‘we ran out of painkillers and had to get creative.’

And don’t get me started on lidocaine infusions. I’ve seen nurses mess up the drip and send someone into cardiac arrest. It’s not magic. It’s risky. And nobody talks about that.

So yeah, cool. You saved 60% on opioids. But how many people got worse because the protocol wasn’t followed? Nobody tracks that.

Also, your ‘low-dose ketamine’? That’s just a fancy way to say ‘we gave them a hallucinogen to shut them up.’

Paul Huppert

January 4, 2026 AT 13:27Really appreciate this breakdown. I’m a physical therapist and I’ve seen patients struggle for weeks because they were left with leftover opioids and no plan. The pre-op stuff makes so much sense-pain starts before the incision. Why wait?

Also, the home care part is huge. So many people get discharged with a 30-day script and no follow-up. That’s how dependency starts. Five-day limit? Yes please.

Hanna Spittel

January 4, 2026 AT 22:24Wait… so they’re giving KETAMINE to regular surgery patients?? 😳 Like… the party drug??

Are we just secretly turning hospitals into underground rave centers??

Also… who’s REALLY in charge of this? Pharma? The government? Are they hiding something??

And why is lidocaine being used like it’s a miracle cure?? It’s a local anesthetic!!

Something’s off… I feel like I’m being gaslit by the medical industrial complex 🤔💊

anggit marga

January 5, 2026 AT 18:57Why is America telling the world how to do pain management when they can't even fix their own healthcare system

My brother had surgery in Lagos and got no meds at all because the hospital ran out

So now you want us to use gabapentin and lidocaine when we can't even get paracetamol

This is just rich

Also who decided opioids are bad anyway

Maybe pain is just part of life

Stop forcing your western ideas on us

Joy Nickles

January 6, 2026 AT 06:39Okay but… I just read this article and I’m confused… why is everyone so obsessed with reducing opioids?? I mean… what if someone actually NEEDS them?? Like… what if they’re in EXCRUCIATING pain?? And the ‘non-opioid’ meds don’t work?? Then what??

Also… who decides what ‘low dose’ means?? Is it 1mg? 5mg? 10mg??

And why is dexmedetomidine even a thing?? It’s not even FDA-approved for this!!

Also… I think the whole thing is a cover-up… I bet the real reason they’re pushing this is because insurance won’t pay for opioids anymore…

And… what if you’re allergic to acetaminophen??

And… what if your kidney is already bad??

And… what if you’re just… tired??

And… why is this even a trend??

…I just feel like I’m being manipulated…

Also… did anyone check the study funding??

…I’m not saying it’s wrong… I’m just saying… I’m suspicious…

…I think I need to talk to someone…

…maybe a therapist…