When a generic drug hits the shelf, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy. But behind every generic pill is a rigorous scientific process designed to prove it works exactly like the brand-name version. That process is called a bioequivalence study. It’s not guesswork. It’s not marketing. It’s hard science-measured in blood samples, statistical models, and tightly controlled clinical trials. And if it fails, the drug doesn’t get approved. Here’s exactly how it’s done.

Why Bioequivalence Matters

Before a generic drug can be sold, regulators like the FDA, EMA, and PMDA need proof that it behaves the same way in the body as the original. This isn’t about ingredients alone. Two pills can have identical active ingredients but different shapes, coatings, or fillers. These differences can change how fast or how much of the drug enters your bloodstream. That’s dangerous if you’re taking something like warfarin or lithium, where tiny changes can cause serious side effects. Bioequivalence studies answer one question: Does the generic deliver the same amount of drug, at the same speed, as the brand? If yes, it’s considered therapeutically equivalent. The FDA estimates that since 2010, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.68 trillion. None of that would be possible without these studies.The Gold Standard: Crossover Design

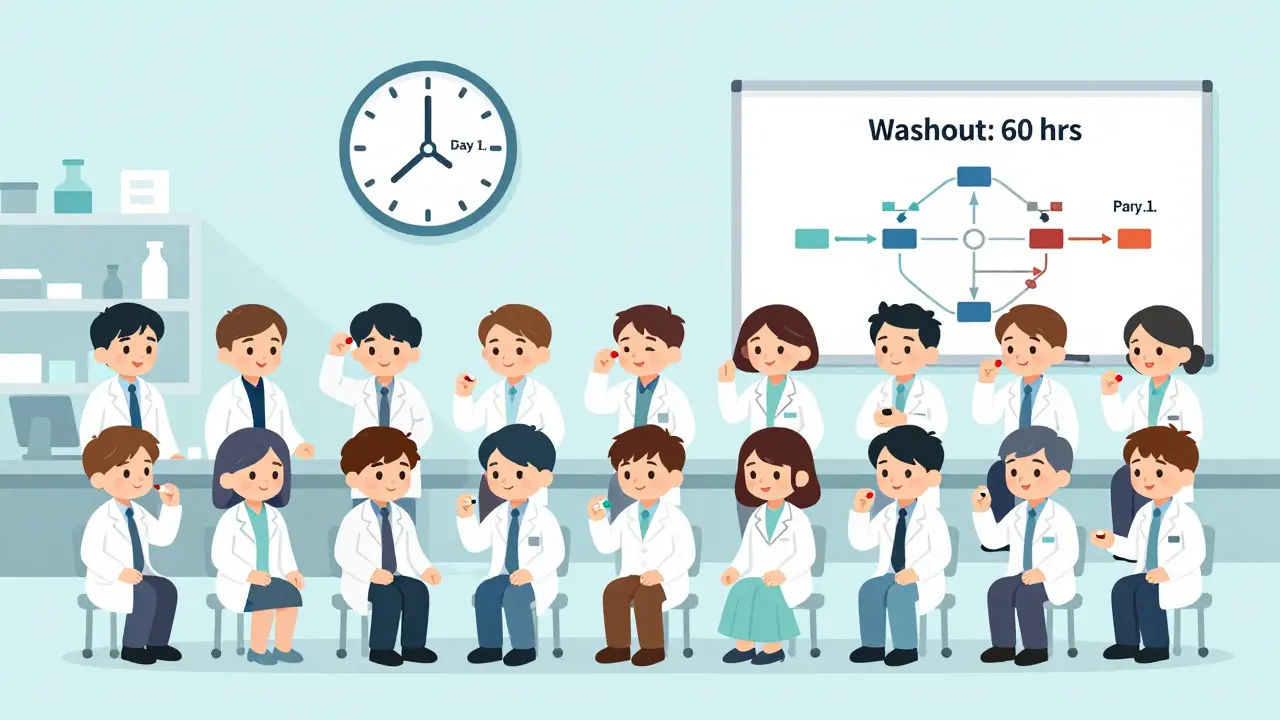

Most bioequivalence studies use a two-period, two-sequence crossover design. That sounds complicated, but here’s what it actually means:- 24 to 32 healthy volunteers (sometimes more, sometimes fewer) sign up.

- Half get the generic drug first, then the brand-name drug after a break.

- The other half get the brand-name drug first, then the generic.

- There’s a washout period between doses-usually five times the drug’s elimination half-life. For a drug that clears in 12 hours, that’s 60 hours. For a long-acting drug like dulaglutide, it could be weeks.

Collecting the Data: Blood Samples and Timing

After each dose, volunteers give blood samples at specific times. The schedule isn’t random. It’s calculated to capture the full journey of the drug in the body.- Before dosing (time zero) - baseline level.

- Just before the expected peak (Cmax) - when the drug hits its highest concentration.

- Two samples around that peak - to map the rise and fall.

- Three or more samples during elimination - to track how the body clears it.

The Numbers That Matter: Cmax and AUC

Two numbers determine success:- Cmax: The highest concentration of drug in the blood.

- AUC(0-t): The total exposure over time, from dosing to the last measurable point.

The Pass/Fail Line: 80%-125%

Here’s the rule: For the study to succeed, the 90% CI for both Cmax and AUC must fall between 80.00% and 125.00%. That means the generic delivers between 80% and 125% of the brand’s exposure. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like phenytoin, digoxin, or cyclosporine-the window tightens to 90.00%-111.11%. These drugs have little room for error. Even a 10% difference could be dangerous. If the CI slips outside those limits, the study fails. No approval. No market. That’s why companies run pilot studies first. According to FDA data, pilot studies cut failure rates from 35% down to under 10%.What Happens When the Drug Is Highly Variable?

Some drugs vary wildly from person to person. Their within-subject coefficient of variation (CV) is over 30%. For these, the standard 80-125% rule doesn’t work well. The EMA requires replicate crossover designs-often four periods with multiple doses of both products. This gives more data to estimate variability. The FDA allows reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which adjusts the acceptance range based on how variable the drug is. Both approaches are scientifically valid but require more subjects-sometimes 50 to 100.Other Study Designs

Crossover isn’t always possible. For drugs with half-lives longer than two weeks, a parallel design is used: one group gets the generic, another gets the brand. No washout needed. But you need more people to compensate for the lack of within-subject comparison. For extended-release products, multiple-dose studies are required. You can’t just give one dose and assume it behaves the same over time. The body builds up the drug, and the release profile must be consistent. In rare cases, pharmacodynamic or clinical endpoint studies are used. For example, with anticoagulants, you measure INR levels. For inhalers or topical creams, you might measure skin absorption or lung deposition. The FDA requires this for certain complex products.Dissolution Testing: The Silent Partner

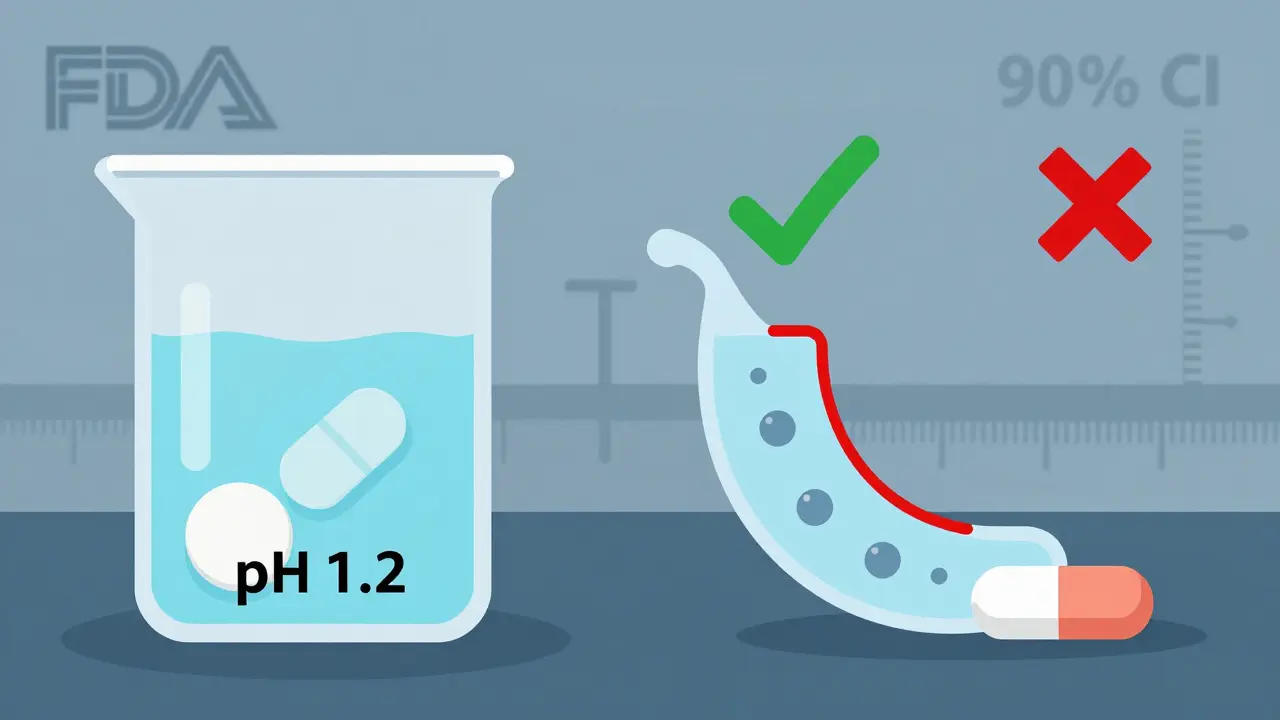

Even if a drug passes the blood test, regulators check how it dissolves. A tablet must release its drug at a similar rate across different pH levels (1.2 to 6.8), mimicking the stomach and intestines. The f2 similarity factor must be above 50. That’s calculated by comparing the dissolution profiles of the generic and brand over time. At least 12 units are tested per condition. If the dissolution curves don’t match, the study fails-even if the blood levels look perfect.

What Goes Wrong?

Bioequivalence studies are expensive and complex. A single failure can cost $250,000 and delay approval by months. Common reasons for failure:- Washout period too short (45% of deficient studies).

- Wrong sampling times (30%).

- Statistical errors or wrong models (25%).

- Unvalidated analytical methods (22% of studies face delays).

Who Runs These Studies?

Most are done by Contract Research Organizations (CROs). These are specialized labs with clinical units, bioanalytical labs, and statisticians trained in bioequivalence models. The FDA processes about 2,500 bioequivalence submissions each year. The average review time is just over 10 months. The people involved need real expertise:- Clinical staff: 6-12 months of BE study experience.

- Biostatisticians: Must know BE-specific ANOVA models.

- Bioanalytical scientists: Must master LC-MS/MS validation.

The Future: Modeling, Simulation, and Waivers

The field is evolving. More studies now use physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling to predict how a drug will behave-cutting down on human testing. The FDA also grants biowaivers for BCS Class I drugs-those that are highly soluble and highly permeable. If the dissolution profile matches and the drug meets these criteria, no blood study is needed. In 2022, 27% of approvals used this route. The FDA’s 2024-2028 plan aims to reduce study requirements by 30% using real-world evidence. But for now, the blood test remains king.Final Thought: It’s Not Magic, It’s Measurement

Bioequivalence studies aren’t about proving a generic is ‘good enough.’ They’re about proving it’s identical in how it works inside the body. Every drop of blood, every hour of sampling, every statistical calculation is there to protect patients. That’s why a generic drug approved in the U.S. works the same as the brand-because science demanded it.What happens if a bioequivalence study fails?

If the 90% confidence interval for Cmax or AUC falls outside 80-125% (or 90-111% for narrow therapeutic index drugs), the study fails. The generic drug cannot be approved. Companies often revise the formulation, run a pilot study, and try again. Failure can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and delay market entry by months or years.

Why are healthy volunteers used instead of patients?

Healthy volunteers eliminate confounding variables like disease states, other medications, or organ dysfunction. This ensures the differences seen are due to the drug formulation-not the patient’s condition. Once bioequivalence is proven in healthy people, it’s assumed to hold in patients too-unless the drug behaves differently in disease states, which is rare for systemic drugs.

Can a generic drug be approved without a bioequivalence study?

Yes, but only in limited cases. For BCS Class I drugs-those that are highly soluble and highly permeable-regulators may grant a biowaiver based on in vitro dissolution testing alone. This applies to a small percentage of drugs (about 27% in 2022). For complex products like inhalers, topicals, or injectables, clinical or pharmacodynamic studies may replace PK studies, but these are exceptions, not the rule.

How long does a typical bioequivalence study take?

A standard two-period crossover study takes 4 to 8 weeks total. Each period lasts 1-3 days (dosing and sampling), with a washout period of 1-4 weeks depending on the drug’s half-life. For long-acting drugs, the entire process can stretch to 3-6 months. The FDA’s review of the submission adds another 10 months on average.

Are bioequivalence studies the same worldwide?

Most countries follow similar principles, but details vary. The FDA allows reference-scaled average bioequivalence for highly variable drugs, while the EMA requires replicate designs. Japan’s PMDA often demands extra dissolution testing. Despite these differences, the core criteria-80-125% CI for Cmax and AUC-are globally accepted. Harmonization through ICH has made studies more consistent across regions.

Juan Reibelo

January 23, 2026 AT 16:12Wow. Just… wow. I had no idea this much science went into generics. I always thought they were just cheaper versions, but this? This is engineering-level precision. Every blood draw, every statistical model, every washout period-it’s like a symphony of control. I’m impressed.

And the 80-125% rule? That’s not arbitrary-it’s *biological* fairness. If your body doesn’t absorb it the same way, it’s not the same drug. Period.

Also, LC-MS/MS? That’s the same tech used in forensics. We’re talking crime-lab accuracy for your Tuesday aspirin.

Marlon Mentolaroc

January 25, 2026 AT 14:11Let me break this down like I’m explaining it to my cousin who thinks ‘generic’ means ‘bad’:

It’s not about cost. It’s about consistency. If the Cmax is off by 10%, you could overdose on warfarin or underdose on epilepsy meds. That’s not ‘maybe’-that’s ‘ICU’.

And the 90% CI? That’s not a suggestion. It’s a legal threshold. FDA doesn’t play. They’ll reject a $250K study over a 0.5% slip. No mercy. No exceptions. Science doesn’t care if you’re a startup or a pharma giant.

Gina Beard

January 25, 2026 AT 16:46Identity through chemistry.

A pill is not a symbol. It’s a kinetic event. The body doesn’t care about branding. Only absorption.

What we call ‘generic’ is really just the unbranded version of a physiological truth.

Pharmaceutical equivalence is the last pure form of objectivity in consumer medicine.

Everything else is marketing. This? This is physics.

Don Foster

January 26, 2026 AT 19:40People don’t get it. Bioequivalence isn’t even that hard. You give people the drug. You take blood. You run stats. Done. Why are we making this sound like rocket science? It’s just pharmacokinetics 101. The FDA overcomplicates it with all these CI rules and washout periods. I’ve seen better data from undergrad labs.

And LC-MS/MS? Please. If you’re not using NMR you’re doing it wrong. But no one cares about NMR anymore because it’s expensive. That’s the real problem. Not the science. The budget.

siva lingam

January 27, 2026 AT 09:00So we spend 6 months and $250k to prove a pill works like another pill. And we call this science. Cool. I’ll take my $3 generic and thank the guy who did the real work-the guy who invented the original. This whole system is just corporate theater. But hey, at least we get to feel smart reading about it.

Shelby Marcel

January 28, 2026 AT 20:25wait so if the drug clears in 12 hrs, washout is 60 hrs?? so like 2.5 days?? that seems long but i guess makes sense??

also why do they use healthy people? like what if the drug is for diabetics or something?? do they just assume it works the same?? feels risky??

and is f2 similarity just a fancy way of saying ‘does it dissolve like the real one?’??

blackbelt security

January 28, 2026 AT 23:05This is the quiet hero of modern medicine.

No one talks about it. No one sees it. But every time you fill a $4 prescription instead of a $400 one, this is why it’s possible.

These studies are the invisible backbone of affordable healthcare.

Respect to the volunteers, the CROs, the statisticians, the LC-MS/MS techs.

You’re not famous. But you’re essential.

Patrick Gornik

January 29, 2026 AT 19:59Let’s not romanticize bioequivalence. It’s a regulatory compromise, not a philosophical triumph. The 80-125% window? That’s not ‘identical’-that’s ‘tolerated’. We’re accepting a 25% variance in exposure and calling it ‘therapeutic equivalence’. That’s not science. That’s capitalism with a lab coat.

And don’t get me started on biowaivers. BCS Class I? That’s a loophole for lazy manufacturers. You’re waiving human data because the drug dissolves too easily? That’s not innovation. That’s abdication.

The real story isn’t the blood draws. It’s the fact that we’ve normalized pharmacological mediocrity and called it progress.

Luke Davidson

January 30, 2026 AT 03:37Reading this made me think about my grandma who takes blood thinners. She used to pay $500/month for the brand. Now she takes the generic and it’s $12. She doesn’t know what Cmax or AUC means. But she knows she’s alive. And that’s what matters.

These studies? They’re not about numbers. They’re about people. The volunteers who give blood. The scientists who stay up all night running assays. The regulators who say ‘no’ when it’s not right.

It’s not sexy. But it’s sacred.

Thank you for writing this. I’m sharing it with my family.

Karen Conlin

February 1, 2026 AT 02:27As someone who’s worked in global health, I’ve seen how this system saves lives in low-income countries. A single successful bioequivalence study can mean thousands of people with HIV or hypertension get life-saving meds at 1/10th the cost.

And yes, the process is rigid. And yes, it’s expensive. But that rigor? It’s the reason we don’t have fake drugs killing people in rural clinics. We’ve got regulators who say ‘no’ to corner-cutting.

Also-healthy volunteers? Genius. If you’re testing a drug that affects liver enzymes, you don’t want someone with cirrhosis muddying the data. You want to isolate the formulation’s effect. That’s not exclusion-it’s precision.

And for the record: the 80-125% range? It’s not arbitrary. It’s based on decades of clinical outcomes. If you change it, you change patient safety. Don’t let the cynics fool you.

asa MNG

February 2, 2026 AT 20:56so like… if the study fails… do they just like… try again?? 😅

and why do they need 24 people?? can’t they just use 5?? like… i mean… it’s just a pill right?? 🤔

also i love how they say ‘washout period’ like its a spa day 😂

also why do they use LC-MS/MS?? can’t they just use a cheap strip?? like… 🤷♂️

also i think this is so cool but also kinda sad that we need so much tech to prove a pill is the same… 😔