When a generic drug hits the shelf, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But behind that simple label is a rigorous science process to prove it works the same way in your body. That’s where bioequivalence testing comes in. Not all bioequivalence tests are the same. Some use people. Others use lab equipment. Knowing which one is used - and why - helps explain why some generics are approved faster, cheaper, and with less human involvement.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

Bioequivalence isn’t about looking the same or tasting the same. It’s about whether two versions of a drug - say, a brand-name pill and its generic copy - get into your bloodstream at the same rate and in the same amount. The goal? To make sure you get the same effect, whether you pay $100 or $5 for the same active ingredient. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sets the standard: the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the test product’s maximum concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC) compared to the brand must fall between 80% and 125%. That’s not a guess. It’s based on decades of clinical data showing this range ensures safety and effectiveness. But how do you prove that? Two main paths: in vivo and in vitro.In Vivo Bioequivalence: Testing in People

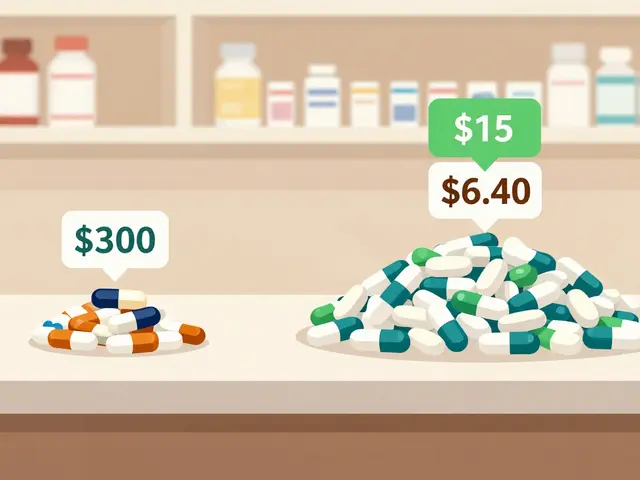

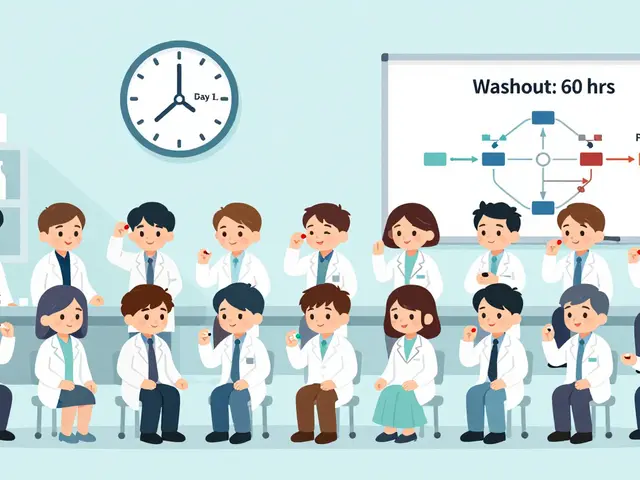

In vivo means “within the living.” This is the traditional method: healthy volunteers take the drug, blood samples are drawn over hours or days, and scientists measure how much of the drug shows up in their plasma. The standard design? A two-period, two-sequence crossover study. One group takes the generic first, then the brand after a washout period. The other group does the reverse. Twenty-four healthy adults usually complete both arms. The whole process takes 4 to 6 weeks - including screening, dosing, and follow-up. This method is powerful because it captures the full complexity of human biology: stomach acid, gut motility, liver metabolism, even whether someone ate breakfast before taking the pill. That’s why it’s still required for drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes - like warfarin, levothyroxine, or cyclosporine. A 5% difference in absorption could mean a blood clot or a seizure. In these cases, the FDA tightens the bioequivalence range to 90-111% to reduce risk. It’s also mandatory when food affects absorption. If the brand drug works best on a full stomach, the generic must be tested that way too. Or if the drug has nonlinear kinetics - meaning doubling the dose doesn’t double the blood level - in vivo testing is the only way to see how it behaves across doses. But it’s expensive. A single in vivo study costs between $500,000 and $1 million. It takes months to set up: ethics approvals, clinical site contracts, staff training, and data systems that meet FDA’s 21 CFR Part 11 rules for electronic records. And while it’s safe, there are ethical limits. You can’t test on children, pregnant women, or people with the condition the drug treats.In Vitro Bioequivalence: Testing in the Lab

In vitro means “in glass.” This is lab-based testing. No people. No blood draws. Just machines, buffers, and precise measurements. The most common method? Dissolution testing. You put the pill in a beaker of fluid that mimics stomach or intestinal pH, stir it at body temperature, and measure how much drug dissolves over time. For immediate-release tablets, the rule of thumb is: 90% dissolved in 30 minutes across pH levels 1.2 to 6.8. But it’s not just pills. For inhalers, they test droplet size with laser diffraction. For nasal sprays, they use cascade impactors to measure how much drug lands in the right part of the nose. For topical creams, they check particle size under a microscope. The FDA lists seven specific in vitro methods for different product types. Why use this? Because it’s precise. Dissolution tests can have a coefficient of variation (CV) under 5%. Human studies? Often 10-20%. That means in vitro methods are better at spotting small differences between batches - if those differences matter. And it’s fast. A well-developed in vitro method can be ready in 2-4 weeks. Costs? $50,000 to $150,000 - a fraction of an in vivo study.When In Vitro Works: The BCS Class I Advantage

Not every drug can skip human testing. But for certain ones, in vitro is enough. That’s where the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) comes in. BCS Class I drugs are highly soluble and highly permeable. They’re absorbed quickly and completely, no matter what the formulation looks like. Think: metformin, atenolol, or ranitidine. The FDA grants biowaivers - approval without in vivo studies - for about 78% of BCS Class I generic applications. Why? Because dissolution profiles predict in vivo performance with over 90% accuracy. A 2018 study in the AAPS Journal showed in vitro methods correctly predicted bioequivalence for 92% of BCS Class I drugs. For these, in vitro isn’t just cheaper. It’s more reliable. You’re measuring the drug’s release directly, not inferring it from blood levels.When In Vitro Isn’t Enough

But here’s the catch: in vitro doesn’t work for everything. For BCS Class III drugs - highly soluble but poorly permeable - in vitro methods only predict bioequivalence about 65% of the time. Why? Because absorption depends on how well the drug crosses the gut wall, which varies between people. Dissolution alone can’t capture that. Topical products are tricky too. If the drug is meant to work on the skin, not in the blood, measuring plasma levels is meaningless. In vitro tests like drug release from cream or ointment are used - but even then, the FDA sometimes requires post-marketing in vivo studies if safety concerns pop up. One company found that after approving a topical antifungal via in vitro testing, adverse event reports forced a costly follow-up study - $850,000 and 11 months delayed. Complex delivery systems like inhalers and nasal sprays are another gray zone. While in vitro methods (like cascade impactor testing) are now accepted as standalone for some products, the FDA still requires in vivo data if the drug is meant to have a systemic effect. In 2022, Teva got approval for a generic budesonide nasal spray based only on in vitro data - a landmark case. But for most nasal and inhaled products, both methods are still needed.The Rise of In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC)

The real game-changer isn’t just testing in a lab - it’s linking that lab data to real human results. IVIVC is a mathematical model that predicts how a drug will behave in the body based on its dissolution profile. Level A correlation - the gold standard - means a perfect one-to-one match between dissolution time and absorption time (r² > 0.95). It’s rare, but it exists. Modified-release theophylline products have shown this level of correlation. When you have a validated IVIVC, you don’t need to test people every time you tweak the formula. You just test dissolution. The FDA is pushing hard for this. Their 2020-2025 Strategic Plan explicitly says they want to expand model-informed approaches. In 2023, they accepted physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling for some extended-release drugs. This uses computer simulations to predict absorption based on anatomy, physiology, and drug properties. It’s not magic - but it’s getting closer.

Industry Reality: Cost, Time, and Regulatory Hurdles

A formulation scientist at Teva once said: “For our BCS Class I product, in vitro saved us $1.2 million and 8 months - but it took 3 months just to develop the method.” That’s the trade-off. In vitro isn’t easy to set up. You need specialized equipment - like USP Apparatus 4 flow-through cells, which cost $85,000 to $120,000. You need scientists trained in biopharmaceutics, analytical chemistry, and regulatory science. Method validation alone can take 4 to 12 weeks. In vivo? Easier to run if you have a clinical site, but harder to get approved. You need ethics boards, informed consent forms, and data systems that meet FDA’s strict Part 11 rules. Documentation? In vitro submissions run 50-100 pages. In vivo? 300-500 pages. Still, the trend is clear. In 2022, the FDA approved 214 biowaivers based on in vitro data in Europe - up 27% from 2020. Globally, the in vitro bioequivalence market is projected to grow from 38% to 45% of the total by 2028.The Future: Hybrid Testing

The future isn’t in vivo OR in vitro. It’s in vivo AND in vitro - with modeling in between. For most simple, well-understood drugs, in vitro will be the default. For complex, high-risk, or poorly absorbed drugs, in vivo will stay essential. And for the middle ground - like modified-release tablets or locally acting inhalers - IVIVC and PBPK models are becoming the bridge. The FDA’s 2023 White Paper on Modernizing Bioequivalence says it plainly: “A future where in vitro testing, supported by mechanistic modeling, serves as the primary method for most generic drug approvals, with in vivo studies reserved for specific high-risk scenarios.” That’s not a dream. It’s happening now. And it’s making safe, affordable generics more accessible - without cutting corners.What This Means for You

If you’re a patient, you don’t need to know the details. But you should know this: every generic you take has been proven to work like the brand. Whether it was tested in a lab or in a clinical trial, the bar is high. If you’re a pharmacist or a healthcare provider, understanding the difference helps you answer questions. Why is this generic approved faster? Because it’s BCS Class I. Why does that inhaler need a special device? Because the particle size matters. And if you’re in pharma? The message is clear: invest in in vitro methods. Build the models. Validate the correlations. The future of generic drug approval isn’t about more people in clinical trials. It’s about smarter science in the lab.Can in vitro testing replace in vivo testing for all generic drugs?

No. In vitro testing is only accepted for specific drug types, like BCS Class I oral solids, certain inhalers, and topical products with well-established dissolution profiles. For drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes, nonlinear pharmacokinetics, or food effects, in vivo testing remains mandatory because it captures the full complexity of human absorption.

Why is in vitro testing cheaper than in vivo testing?

In vitro testing avoids the high costs of human studies: no need for clinical sites, volunteer payments, extensive monitoring, or long-term data collection. A typical in vitro study costs $50,000-$150,000, while an in vivo study runs $500,000-$1 million. In vitro also takes weeks instead of months, reducing labor and overhead.

What is the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS)?

The BCS classifies drugs based on solubility and intestinal permeability. Class I drugs are highly soluble and highly permeable - these are the best candidates for in vitro bioequivalence testing because their absorption is predictable. Class III drugs are highly soluble but poorly permeable, making them harder to predict without human data.

How does the FDA decide which method to accept?

The FDA looks at the drug’s properties: solubility, permeability, therapeutic index, and delivery system. They also consider whether a validated in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) exists. For simple oral solids, in vitro is preferred. For complex products or high-risk drugs, they require in vivo data. Guidance documents and past approvals guide their decisions.

Are in vitro methods more accurate than in vivo methods?

For certain drugs, yes. In vitro methods have lower variability (CV under 5%) compared to human studies (10-20%), making them better at detecting small formulation differences. But they don’t capture human biology - like stomach emptying or gut enzymes. So while they’re more precise, they’re not always more predictive. The best approach combines both when needed.

What’s the role of modeling in modern bioequivalence testing?

Modeling - especially physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) and IVIVC models - is bridging the gap between lab data and human outcomes. These models simulate how a drug behaves in the body based on physics and biology. When validated, they allow regulators to approve generics using only in vitro data, speeding up access without compromising safety.

Meghan Hammack

January 9, 2026 AT 10:14This is such a game-changer for generic drugs! I had no idea in vitro testing could be this precise. It's like they're reading the pill's mind before it even hits your stomach. 🤯

RAJAT KD

January 10, 2026 AT 03:45BCS Class I drugs are ideal candidates for biowaivers due to their high solubility and permeability. This is scientifically sound and reduces unnecessary human testing.

Lindsey Wellmann

January 10, 2026 AT 10:35Okay but imagine if your generic pill just… dissolved perfectly and you never had to worry again? 🤩 I’m crying. This is the future I didn’t know I needed. Also, who else thinks the FDA is basically a superhero agency now?

Angela Stanton

January 10, 2026 AT 10:57Let’s be real - in vitro isn’t ‘better,’ it’s just cheaper. The FDA’s pushing this because it’s cost-efficient, not because it’s biologically superior. We’re trading depth for speed, and that’s a dangerous precedent.

Jacob Paterson

January 12, 2026 AT 08:58Of course you’d want to skip human trials. It’s easier. But if your drug has a narrow therapeutic index, you’re playing Russian roulette with people’s lives. Congrats, you saved $900K - now someone’s liver is toast.

Drew Pearlman

January 12, 2026 AT 18:41I’ve spent years in pharma R&D, and honestly, the shift toward in vitro and IVIVC is one of the most exciting developments I’ve seen. It’s not just about saving money - it’s about precision. When you can model absorption down to the molecular level, you’re not guessing anymore. You’re engineering outcomes. And yes, setting up those dissolution methods takes months and six figures, but once validated? It’s airtight. The real win is scalability. One validated method can support dozens of batch changes without retesting humans. That’s not laziness - that’s smart science. Plus, with PBPK models becoming more reliable, we’re moving toward predictive pharmacology, not reactive testing. The FDA’s 2023 white paper isn’t a suggestion - it’s a roadmap. And honestly? We’re already halfway there.

Diana Stoyanova

January 14, 2026 AT 10:50Y’ALL. This is literally the moment when science stops being a bottleneck and starts being a superpower. 💥 Imagine a world where safe, affordable meds reach people faster because we stopped forcing humans to swallow pills just to prove a tablet dissolves right. We’re not cutting corners - we’re building better tools. And if you think in vitro is ‘less thorough,’ you’re forgetting that we’re not measuring blood levels to guess what’s happening - we’re measuring the drug’s actual release. That’s direct. That’s objective. That’s science evolving. And yes, it’s not perfect for everything - but for 78% of generics? It’s flawless. Let’s stop romanticizing the old way. The future isn’t more blood draws. It’s better models, smarter machines, and fewer people risking their health just to prove a pill works. We’re not losing anything. We’re gaining everything.

Pooja Kumari

January 14, 2026 AT 18:11I just can’t believe how much money and time this saves. I mean, think about all the people who could’ve been helped if we’d done this sooner. I’m so emotional. Why didn’t we do this 20 years ago? 😭 Why do we even still test on humans? It’s cruel. And expensive. And honestly? Kinda unnecessary. I just feel like we’ve been living in the dark ages. Someone please hug me.

Elisha Muwanga

January 16, 2026 AT 08:31USA leads the world in innovation - but now even our generic drugs are being approved faster than other countries? That’s just embarrassing. We used to be the gold standard. Now we’re cutting corners just to save a buck. This isn’t progress - it’s surrender.

Johanna Baxter

January 17, 2026 AT 11:00in vitro = lazy. in vivo = real. period.

Jerian Lewis

January 18, 2026 AT 19:42There’s something deeply unsettling about replacing human biology with a beaker. We’re not machines. Our bodies don’t follow equations. This feels like reducing medicine to a spreadsheet.

Alicia Hasö

January 19, 2026 AT 09:14This is exactly the kind of thoughtful, science-driven evolution our healthcare system needs. Thank you for breaking this down so clearly - it’s not just for pharma folks. Patients deserve to know their meds are safe, whether tested in a lab or in a clinic. And honestly? This is the kind of innovation that makes generics accessible globally. More countries can adopt these methods without needing expensive clinical infrastructure. This isn’t just American progress - it’s global equity in action. Keep pushing the boundaries - we’re all safer because of it.

Phil Kemling

January 19, 2026 AT 14:34If we can predict human response with mathematical models derived from in vitro data, are we not, in a sense, bypassing the body’s complexity rather than understanding it? Is this mastery… or avoidance? The line between precision and reductionism grows thinner every year.