Every day, millions of people take generic drugs without even realizing it. They’re the affordable pills on the pharmacy shelf, often in plain white or blue packaging, costing a fraction of the brand-name version. But how do these drugs end up in your medicine cabinet? And how can they be so much cheaper - yet still work the same way?

What Makes a Drug ‘Generic’?

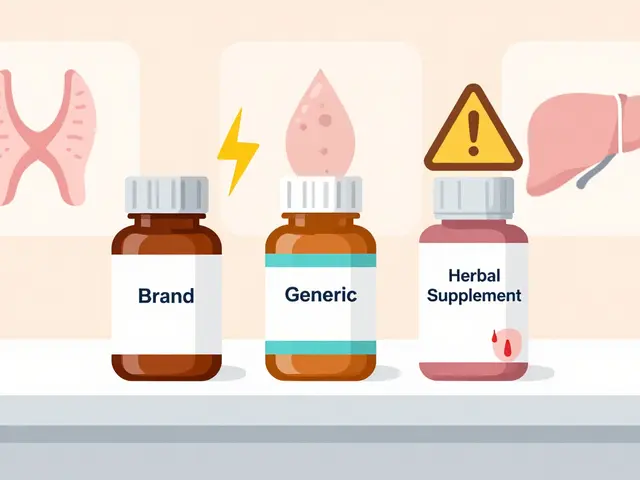

A generic drug isn’t a copycat. It’s not a knockoff. It’s a scientifically proven duplicate of a brand-name drug. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires that generic drugs contain the exact same active ingredient, in the same strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the original. That means if you’re taking a generic version of lisinopril for high blood pressure, it’s chemically identical to the brand-name Zestril. The only differences? The color, shape, flavor, or inactive ingredients - like fillers or coatings - which don’t affect how the drug works in your body. The legal backbone of this system is the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act. Before this law, companies had to repeat all the expensive clinical trials done by the original drugmaker. That made generics too costly to produce. Hatch-Waxman changed that by creating the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. It lets generic manufacturers skip human trials for safety and effectiveness - because those were already proven by the brand-name drug. All they need to prove is bioequivalence: that their version gets into your bloodstream at the same rate and to the same level as the original. Today, about 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. Over the past decade, they’ve saved the healthcare system more than $1.7 trillion.The First Step: Reverse Engineering the Original

Before a single pill is made, manufacturers start by studying the brand-name drug - called the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). This isn’t just looking at the label. It’s full chemical and physical analysis. Teams use advanced tools like HPLC (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography) and mass spectrometry to break down the drug into its components. They figure out:- The exact chemical structure of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API)

- The type and amount of each inactive ingredient (excipients) like lactose, starch, or magnesium stearate

- How the drug is formulated - is it a tablet? A capsule? A delayed-release coating?

- The dissolution profile - how quickly the drug dissolves in simulated stomach fluid

Designing the Formula: Quality by Design (QbD)

Modern generic drug manufacturing doesn’t rely on trial and error. It uses Quality by Design (QbD), a framework endorsed by the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). QbD means you design the drug with quality built in from the start. Here’s how it works:- Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): These are the measurable characteristics that affect safety and effectiveness - like how much drug is released over time, or how stable it is under heat.

- Critical Material Attributes (CMAs): These are the properties of raw materials that influence CQAs. For example, the crystal form of the API or the moisture content of a filler.

- Critical Process Parameters (CPPs): These are the settings in the manufacturing equipment - like mixing speed, compression pressure, or drying temperature - that directly impact CQAs.

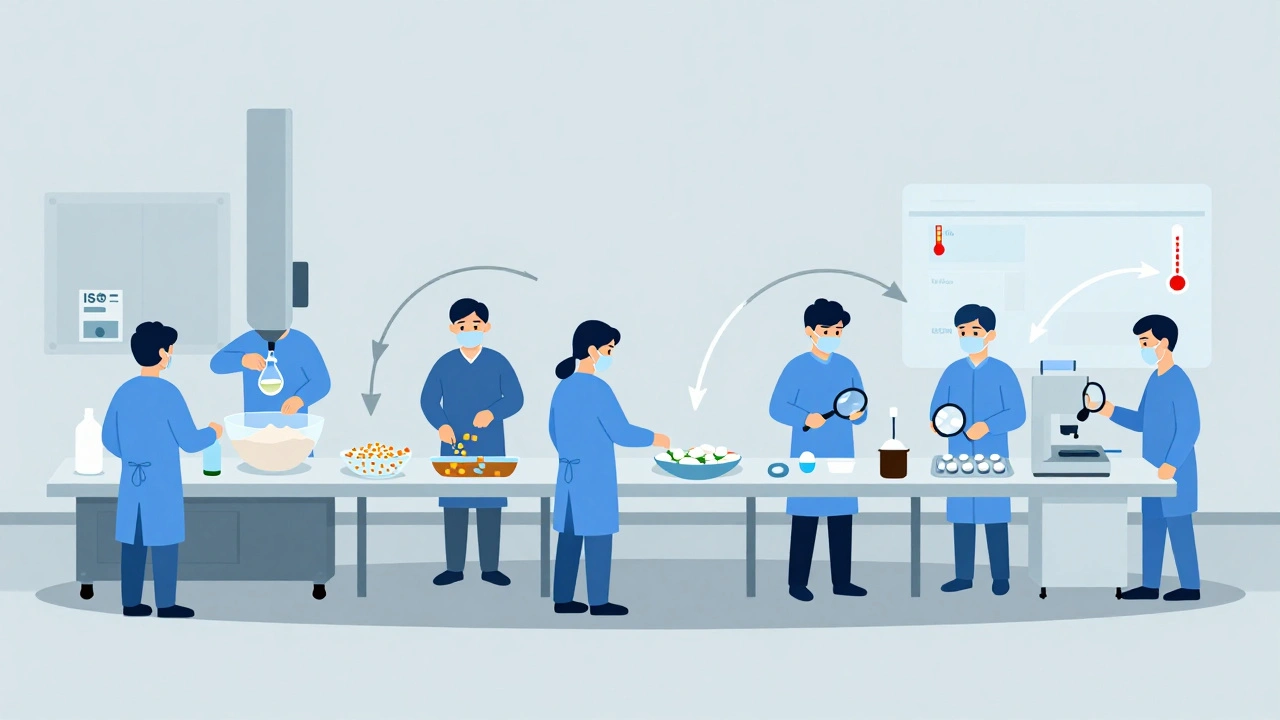

The Manufacturing Process: 7 Key Steps

Once the formula is locked in, production begins. Here’s what happens in a typical generic drug manufacturing facility:- Formulation: The active ingredient and all excipients are weighed precisely. Even a 0.1% error can lead to a batch being rejected.

- Mixing and Granulation: Powders are blended in large tumblers. For tablets, the mixture is turned into granules - small clumps that flow better and compress evenly. This is done with wet granulation (adding liquid) or dry granulation (using rollers).

- Drying: If wet granulation was used, the granules are dried in ovens at controlled temperatures. Moisture must be reduced to below 2% to prevent degradation and ensure stability.

- Compression and Encapsulation: For tablets, granules are pressed into shape using high-speed tablet presses. Each tablet must weigh within ±5% for pills under 130mg, or ±7.5% for pills between 130-324mg. Capsules are filled using automated machines that drop precise amounts of powder into gelatin shells.

- Coating: Many tablets get a thin film coating. This hides the taste, protects the drug from moisture, or controls how fast it releases in the gut. Some coatings are enteric - meaning they only dissolve in the intestines, not the stomach.

- Quality Control: Every batch is tested at multiple stages. Samples are checked for identity, strength, purity, dissolution rate, and microbial contamination. Dissolution testing is especially important: the drug must release between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s release profile over time.

- Packaging and Labeling: Tablets or capsules are sealed in blister packs or bottles. Labels must match the brand-name drug’s wording exactly - including warnings, dosage instructions, and active ingredient name. But they can’t look identical. U.S. trademark law forbids generics from copying the shape, color, or logo of branded drugs.

Regulatory Hurdles: The ANDA Pathway

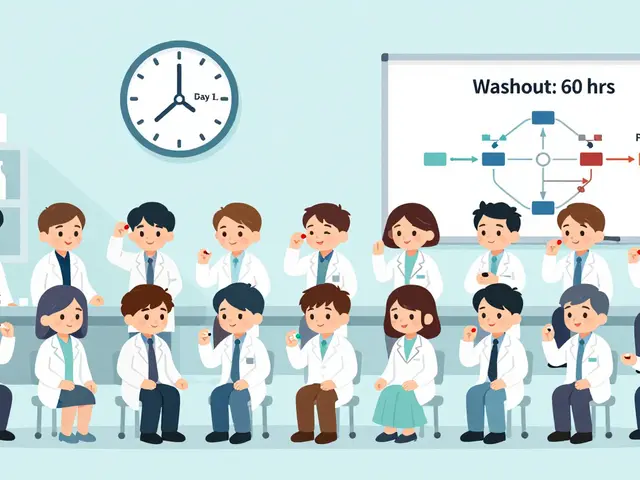

Getting approval isn’t just about making the drug. It’s about proving it’s equivalent - and that your factory can make it safely, every time. The ANDA application includes:- Proof of bioequivalence from human studies - usually 24 to 36 healthy volunteers

- Detailed descriptions of the manufacturing process

- Results from stability testing (how the drug holds up over time under different temperatures and humidity)

- Documentation showing compliance with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP)

Quality Control: More Than Just Testing

A generic drug plant isn’t just a factory. It’s a tightly controlled environment. CGMP rules require:- Temperature-controlled rooms (20-25°C)

- Humidity kept between 45%-65% RH

- Cleanrooms classified as ISO Class 5-8, depending on the stage

- Staff wearing gowns, masks, and gloves

- Equipment cleaned and validated after every batch

- Inadequate investigation of out-of-specification results (37% of warning letters)

- Insufficient process validation (29%)

- Lack of quality unit oversight (24%)

Challenges and Controversies

Not all generics are created equal - and not all are easy to make. Simple generics - like metformin or atorvastatin - have dozens of manufacturers. Prices drop fast. Within two years, they can lose 70-80% of their value. But complex generics - like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams - are harder to copy. Only a few companies can make them. That’s why the FDA launched its Complex Generic Products Initiative in 2022. So far, it’s published 127 product-specific guidances to help manufacturers navigate tricky formulations. One case study showed a generic version of Clobetasol Propionate - a topical steroid - took 7 years and $47 million to develop because matching the skin penetration profile was nearly impossible. That’s why some experts, like Dr. Gary Buehler, say: “The biggest challenge today is demonstrating equivalence for complex products where in vitro testing can’t predict in vivo performance.” There’s also concern about where the ingredients come from. As of 2023, 78% of the active ingredients in U.S. generic drugs are made in China and India. That raises questions about supply chain risks - especially after pandemic-related disruptions. But for most patients, the results speak for themselves. A 2023 survey by the Association for Accessible Medicines found 89% of pharmacists have high confidence in generic drug quality. Only 3% reported any meaningful difference in patient outcomes.The Future: Automation, AI, and Faster Production

The industry is changing. The FDA’s Emerging Technology Program has approved 17 facilities using continuous manufacturing - a method where drugs are made in a constant flow, not in batches. This reduces production time from weeks to hours and cuts waste. Vertex’s cystic fibrosis drug, made this way, achieved 99.98% batch acceptance - far higher than traditional methods. AI is also stepping in. Pfizer ran a pilot using machine vision to inspect pills for defects. It cut visual inspection errors by 40%. Digital twins - virtual models of manufacturing lines - are being tested to predict problems before they happen. GDUFA IV, the latest funding agreement with the FDA, now requires 90% of ANDAs to be reviewed within 10 months - down from 17. That’s speeding up access to affordable drugs.Why It Matters

Generic drugs aren’t just cheaper. They’re essential. Without them, millions of people couldn’t afford insulin, blood pressure pills, or antibiotics. The savings aren’t theoretical - they’re life-changing. A generic version of Sovaldi, a hepatitis C drug, dropped the cost from $84,000 per course to $28,000. That made treatment possible for people who would have otherwise gone without. The system isn’t perfect. There are gaps. Supply chains are fragile. Some complex drugs still take too long to reach the market. But the core principle holds: if you can prove a drug works the same way, it should cost the same - or less. The next time you pick up a generic prescription, remember: it’s not a compromise. It’s science - carefully engineered, rigorously tested, and legally required to be just as effective as the brand-name version.Are generic drugs as safe and effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to meet the same strict standards for safety, strength, quality, and performance as brand-name drugs. They must demonstrate bioequivalence - meaning they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate. Over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics, and studies consistently show no meaningful difference in clinical outcomes for most patients.

Why are generic drugs so much cheaper?

Generic drugs don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials because they rely on the brand-name drug’s existing safety and effectiveness data. The approval process (ANDA) costs $5-10 million per drug, compared to $2.6 billion for a new brand-name drug. Manufacturing costs are also lower due to competition - often dozens of companies make the same generic, driving prices down. Plus, they don’t spend money on advertising or branding.

Can different generic versions of the same drug work differently?

All approved generics must meet the same bioequivalence standards, so they should work the same. But because they can use different inactive ingredients or manufacturing methods, some patients - especially those on narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine - may notice small differences in how their body responds. If you switch generics and feel different, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. You can usually request the same manufacturer if needed.

What does ‘bioequivalence’ mean?

Bioequivalence means that a generic drug releases its active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate and to the same extent as the brand-name drug. This is measured by comparing two key values: Cmax (peak concentration) and AUC (total exposure over time). The generic’s values must fall within 80%-125% of the brand-name drug’s, with 90% confidence. If it’s outside that range, the FDA won’t approve it.

Are all generic drugs made in the U.S.?

No. As of 2023, 78% of the active ingredients in U.S. generic drugs come from China and India. Finished dosage forms (pills, capsules) are also often manufactured overseas. However, all facilities - whether in the U.S., India, or China - must pass FDA inspections and meet the same Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP) standards. The FDA inspects over 3,000 foreign facilities annually.

How long does it take to make a generic drug from idea to market?

For a simple generic, it typically takes 3-4 years and $5-10 million. This includes formulation development, bioequivalence testing, regulatory submission, and facility inspections. Complex generics - like inhalers or injectables - can take 7-10 years and cost over $50 million. The FDA’s review time averages 17 months, but can stretch to 36 months for complicated products.

Kaitlynn nail

December 10, 2025 AT 20:03Ben Greening

December 11, 2025 AT 20:49Raj Rsvpraj

December 13, 2025 AT 02:36Jack Appleby

December 14, 2025 AT 01:27Frank Nouwens

December 15, 2025 AT 05:34Aileen Ferris

December 15, 2025 AT 11:33Rebecca Dong

December 17, 2025 AT 09:35Stephanie Maillet

December 17, 2025 AT 13:04David Palmer

December 18, 2025 AT 15:11Michaux Hyatt

December 20, 2025 AT 04:17Michelle Edwards

December 21, 2025 AT 10:41Nikki Smellie

December 22, 2025 AT 08:47Queenie Chan

December 23, 2025 AT 23:16Doris Lee

December 25, 2025 AT 06:56Sarah Clifford

December 25, 2025 AT 11:29