Most people assume pharmacies make the most money off expensive brand-name drugs. But the truth is the opposite. Generics - the cheap, no-name versions of pills you pick up for $4 or $10 - are what keep most pharmacies open. They don’t make much per pill, but they make way more profit per prescription than brand drugs. That’s the strange math behind pharmacy economics today.

Why Generics Are the Real Profit Engine

Generic drugs make up about 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. But they only account for 25% of total drug spending. Why? Because brand-name drugs cost hundreds or even thousands of dollars per prescription, while generics cost $5 to $20. Pharmacies don’t need to sell many brand-name drugs to make money - they just need to sell a lot of generics.

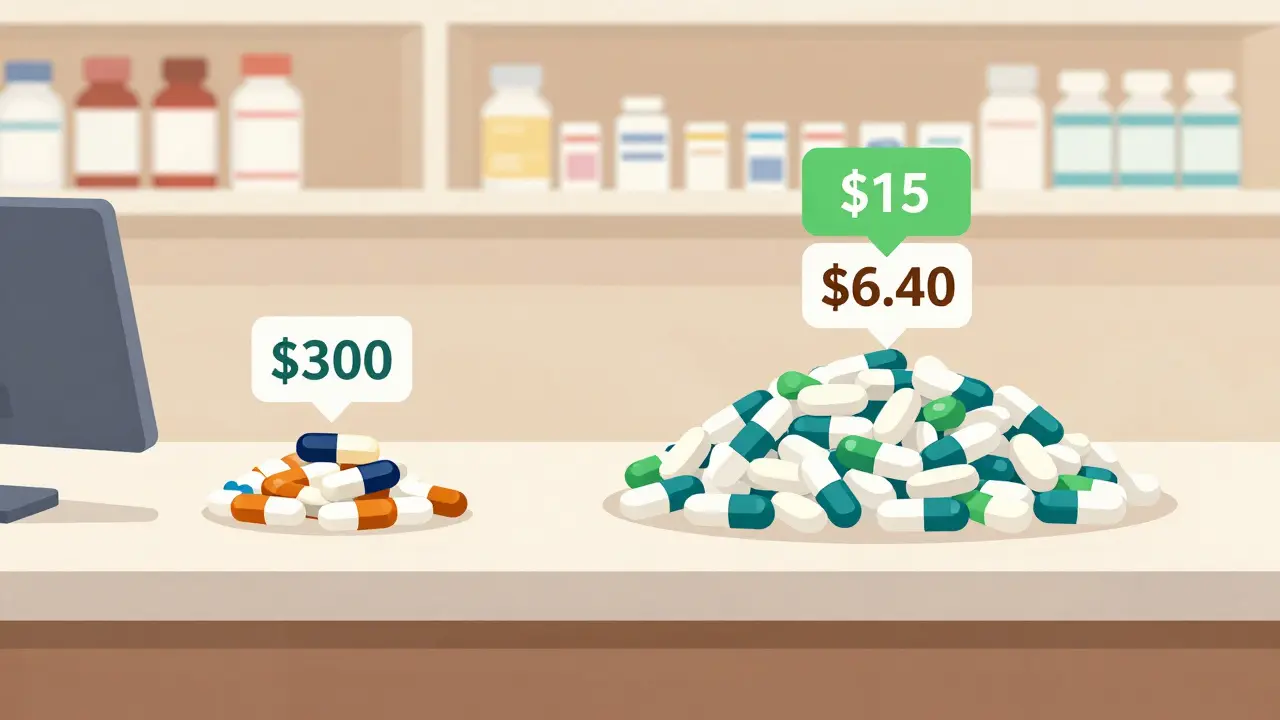

The numbers don’t lie. On average, pharmacies make a 42.7% gross profit margin on generic drugs. For brand-name drugs? Just 3.5%. That’s more than 12 times the profit. A $15 generic prescription might net a pharmacy $6.40. A $300 brand drug? Maybe $10.50. So even though the brand drug costs 20 times more, the pharmacy walks away with less than half the profit.

This isn’t a glitch - it’s how the system was built. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created a fast track for generic drugs to enter the market. The idea was to drive down prices through competition. And it worked. But over time, the profit structure shifted. Manufacturers of brand drugs kept high margins, while pharmacies became the main beneficiaries of generic markups.

Who Really Gets Paid?

It’s easy to blame pharmacies for high drug prices. But the real money isn’t always in the pharmacy’s register. The entire supply chain - manufacturers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), wholesalers - all take cuts. And they take bigger ones from brand drugs.

Manufacturers make about 76% gross profit on brand-name drugs. On generics? Only 50%. That’s because brand drugs are protected by patents and can be priced however the company wants. Generics? Once the patent expires, dozens of companies start making the same pill. Prices crash. But here’s the twist: when prices drop, pharmacies still get to mark them up by 40% or more.

Meanwhile, PBMs - the middlemen between insurers and pharmacies - are the real profit kings in the generic game. They charge insurers more than they pay pharmacies, pocketing the difference. This is called “spread pricing.” For a $10 generic, a PBM might charge the insurer $25 but pay the pharmacy $12. That $13 spread? That’s pure PBM profit. And since generics are dispensed so often, those spreads add up fast.

Wholesalers and mail-order pharmacies make even more. Some mail-order outlets make 1,000 times more profit on certain generics than a small-town pharmacy does. That’s why big chains and mail-order services are growing - they have the scale to negotiate better deals and absorb the losses from low reimbursements.

The Independent Pharmacy Crisis

Small, independent pharmacies are getting crushed. They fill the most prescriptions, but they get the worst reimbursement. In 2015, their gross margin on generics was around 24.6%. By 2022, it dropped to 19.8%. And after rent, payroll, insurance, and utilities? Many are left with just 2% net profit - sometimes less.

One Ohio pharmacy owner told Pharmacy Times: “My net profit on generics has dropped from 8-10% five years ago to barely 2% now, while my overhead has increased 35%.” That’s not a typo. He’s working 60-hour weeks to make less than minimum wage on the most common prescriptions he dispenses.

Why? PBMs use “clawbacks.” That’s when a pharmacy gets paid $12 for a generic, but later the PBM says, “Oops, we overpaid. Give back $5.” Suddenly, the pharmacy loses money on a prescription they thought they made $6 on. These clawbacks are legal, hidden in fine print, and happen daily.

Then there’s the “single-source” problem. When only one company makes a generic, competition vanishes. Prices spike. In some cases, a single-source generic now costs more than the original brand drug. That’s not a market failure - it’s a market collapse.

How Pharmacies Are Fighting Back

Some pharmacies aren’t waiting for Congress to fix this. They’re changing their business models.

- Some are dropping PBM contracts entirely and going cash-only for generics. Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company charges $20 for a generic plus a $3 dispensing fee. No middlemen. No spreads. Just cost + markup. It’s working - they now fill over a million prescriptions a month.

- Others are adding medication therapy management (MTM) services. Pharmacists sit down with patients to review all their drugs, catch interactions, and help with adherence. Insurance pays $50-$100 per session. That’s real revenue - not a margin on a $5 pill.

- A few are becoming specialty pharmacies. Instead of selling aspirin, they handle complex drugs for cancer, MS, or rare diseases. These drugs come with higher reimbursements and fewer competitors.

- Some are partnering directly with employers. Instead of going through Blue Cross or UnitedHealth, a local pharmacy signs a contract with a factory or school district to offer flat-rate pricing for employees. No PBM. No clawbacks.

These strategies aren’t easy. They take time, training, and courage. But they’re working. Pharmacies using these methods report 3-5% higher net margins than those stuck in the old PBM system.

The Bigger Picture: Regulation and Change

The government is starting to pay attention. The FTC has launched investigations into PBM practices. Several states - California, Texas, Illinois - passed laws in 2022-2023 requiring PBMs to disclose their reimbursement formulas. No more hidden spreads.

The Inflation Reduction Act, starting in 2026, will let Medicare negotiate prices for some high-cost drugs. That won’t directly affect generics, but if brand drug prices fall, insurers may pressure PBMs to lower their spreads - which could trickle down to pharmacies.

Meanwhile, the FDA approved over 2,400 new generic drugs between 2018 and 2020. That’s good for patients - it saved $161 billion. But it also means more competition, which squeezes margins even further. It’s a catch-22: more generics = lower prices = less profit for pharmacies.

What’s Next?

The future of pharmacy economics is split. On one side: consolidation. Chains and mail-order services will keep growing. Independent pharmacies? The National Community Pharmacists Association estimates 3,000 closed between 2018 and 2023. Without reform, another 20-25% could disappear by 2027.

On the other side: innovation. Transparent pricing models, direct contracting, and value-based services are proving that pharmacies can survive - even thrive - without relying on the broken PBM system.

For patients, this means more choices. You might pay $5 for a generic at Amazon Pharmacy, $12 at your local pharmacy with a flat fee, or $25 through your insurer’s mail-order service. The price isn’t about the drug. It’s about who controls the money flow.

Generics aren’t the problem. They’re the solution - to affordability, to access, to competition. But the system that handles them is broken. Until pharmacies get paid fairly for the work they do - not just the pills they hand out - this imbalance will keep hurting patients, pharmacists, and communities alike.

Why do pharmacies make more profit on cheap generics than expensive brand drugs?

Pharmacies make higher gross margins on generics because they’re sold in high volume at low prices, and the markup percentage is much larger. A $10 generic with a 40% margin nets $4. A $300 brand drug with a 3.5% margin nets just $10.50. Even though the brand drug costs more, the pharmacy’s profit is smaller. Generics are the volume play - and volume wins.

What is spread pricing, and how does it hurt pharmacies?

Spread pricing is when a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) charges an insurance plan more for a drug than it pays the pharmacy. The difference - the “spread” - goes to the PBM as profit. For example, the PBM charges the insurer $25 for a $10 generic but pays the pharmacy only $12. The pharmacy loses $3 if they’re not careful. This practice hides true costs and squeezes pharmacy profits, especially for independents.

Why are some generic drugs more expensive than brand-name versions?

When only one manufacturer makes a generic - called a “single-source” generic - competition disappears. Without other companies undercutting prices, the single maker can raise costs. In some cases, these single-source generics cost more than the original brand drug. This happened with drugs like doxycycline and cyclosporine, where supply issues and consolidation led to price spikes.

What are clawbacks, and why do they happen?

Clawbacks are when a PBM later demands money back from a pharmacy after paying for a prescription. This happens when the PBM’s system shows the pharmacy was overpaid - often because the PBM changed the reimbursement rate after the fact. The pharmacy has already paid the wholesaler and given the drug to the patient. Now they’re on the hook for the difference. It’s a hidden cost that turns profitable prescriptions into losses.

Can independent pharmacies survive without PBMs?

Yes - but it’s hard. Some have cut out PBMs entirely and switched to direct cash pricing, employer contracts, or subscription models. Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company and Amazon Pharmacy show it’s possible. These pharmacies charge transparent prices - cost + dispensing fee - and bypass the PBM system. Patients pay less, and pharmacies earn predictable margins. But it requires trust, marketing, and operational changes most small pharmacies aren’t equipped for.

What You Can Do

If you’re a patient, ask your pharmacist: “Is this covered by my insurance, or can I pay cash?” Sometimes cash is cheaper. If you’re on a fixed income, ask about patient assistance programs. Many drugmakers offer discounts on brand drugs - and some pharmacies have generic-only cash programs.

If you’re a pharmacy owner, explore direct contracting. Join your state’s pharmacy association. Learn about MTM billing. Challenge clawbacks. Use tools like the NCPA’s Rebuttal Academy to fight unfair PBM decisions.

Generics are supposed to save money. But right now, the system is saving money for PBMs - not patients or pharmacies. Fixing that starts with understanding how the money moves. And that’s the first step to change.

Jarrod Flesch

January 20, 2026 AT 17:50Kelly McRainey Moore

January 21, 2026 AT 06:17Ashok Sakra

January 21, 2026 AT 16:16Gerard Jordan

January 23, 2026 AT 12:41michelle Brownsea

January 23, 2026 AT 23:35Roisin Kelly

January 25, 2026 AT 18:18Malvina Tomja

January 26, 2026 AT 06:57Samuel Mendoza

January 27, 2026 AT 15:09Glenda Marínez Granados

January 29, 2026 AT 06:22Yuri Hyuga

January 31, 2026 AT 04:28MARILYN ONEILL

January 31, 2026 AT 10:23Coral Bosley

January 31, 2026 AT 15:33