When your doctor prescribes a medication like levothyroxine, warfarin, or tacrolimus, you might assume that the brand name is the only safe option. But what if your pharmacy automatically swaps it for a cheaper generic? For drugs with a Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI), this question isn’t just about cost-it’s about safety.

NTI drugs are not like your average blood pressure pill or antibiotic. They have a razor-thin line between working and causing harm. A tiny change in how much of the drug gets into your bloodstream-just 5% or 10%-can mean the difference between control and crisis. For someone on warfarin, that could mean a stroke or dangerous bleeding. For someone on levothyroxine, it could mean fatigue, weight gain, or heart rhythm problems. And for transplant patients on tacrolimus? It could mean organ rejection.

The FDA says generics must be just as safe and effective as brand-name drugs. But for NTI drugs, the rules are stricter. Since 2014, the FDA requires generic versions to meet tighter bioequivalence standards-sometimes as narrow as 90% to 111% of the brand’s concentration levels. That’s far more precise than the usual 80%-125% range used for most medications. Still, even with these standards, real-world data shows mixed results.

What Makes an NTI Drug Different?

Not all drugs are created equal. Most medications have a wide safety margin. If you take a little more or less, your body can handle it. But NTI drugs don’t give you that room. Their therapeutic window-the range between the dose that works and the dose that’s toxic-is extremely small.

Common NTI drugs include:

- Levothyroxine (for hypothyroidism)

- Warfarin (a blood thinner)

- Tacrolimus (used after organ transplants)

- Phenytoin and Carbamazepine (antiseizure drugs)

- Lithium (for bipolar disorder)

These drugs are used for life-threatening or chronic conditions. They require careful monitoring. Even a small shift in how your body absorbs or metabolizes the drug can throw off your entire treatment plan.

Are Generic NTI Drugs Really the Same?

Manufacturers claim they are. The FDA approves them based on bioequivalence studies-tests that measure how much of the drug enters your bloodstream and how fast. For most drugs, a 20% difference in absorption is acceptable. For NTI drugs, the acceptable range is often cut in half.

But here’s the catch: bioequivalence doesn’t always mean clinical equivalence. A study of over 17,000 patients on levothyroxine found no significant difference in thyroid hormone levels between brand and generic users. That’s reassuring. Another study of 3.5 million people showed similar outcomes for generics in treating diabetes, high blood pressure, and depression.

But then you look at tacrolimus. Studies show that switching between different generic versions-even those approved by the FDA-can cause spikes or drops in blood levels. Transplant centers now require weekly blood tests for months after a switch. One pharmacist told me, “I’ve seen patients lose their new kidney because their tacrolimus level dropped after a generic switch they didn’t even know about.”

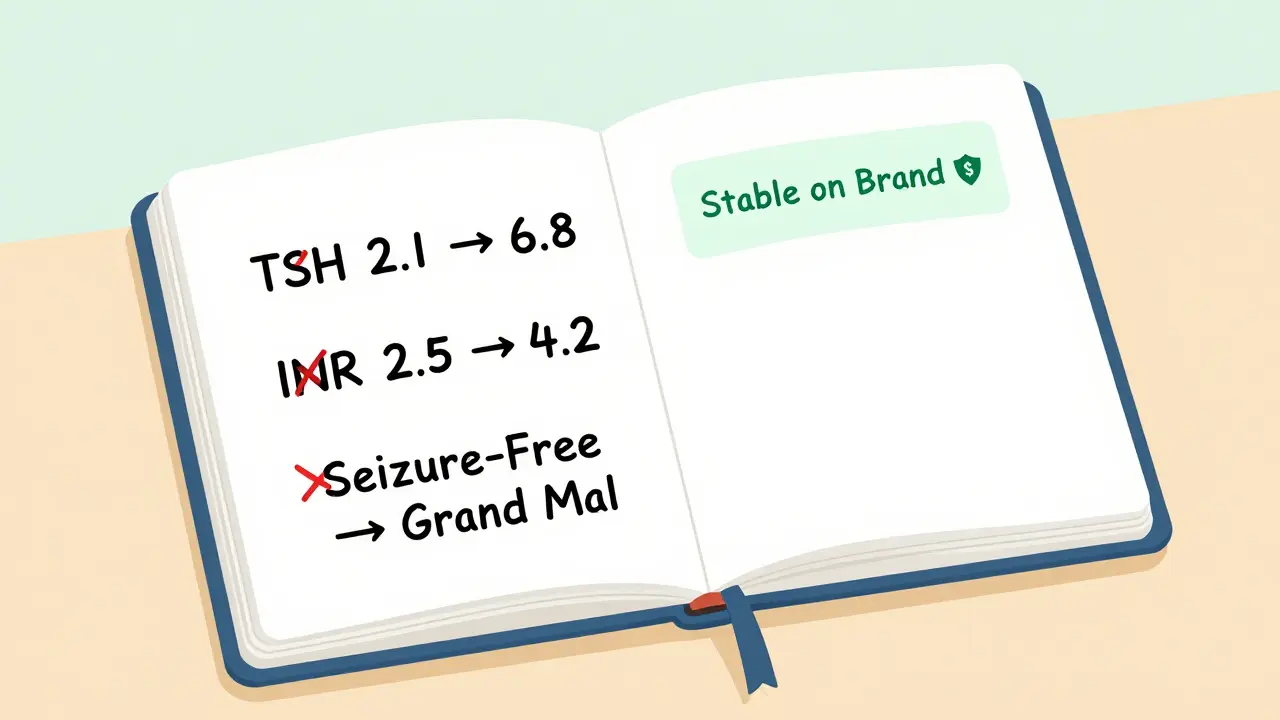

And for antiseizure drugs? The data is messy. A 2022 survey by the Epilepsy Foundation found 42% of patients reported breakthrough seizures after switching to a generic. While some of that may be coincidence, others say it’s real. One patient on Reddit wrote, “I’d been seizure-free for five years on brand. Switched to generic. Two weeks later, I had a grand mal. Took three months to get back on track.”

What Do Experts Really Say?

The FDA stands by its approval process. Former Director Dr. Janet Woodcock said, “The evidence invalidates the widespread theory of the clinical superiority of brand-name drugs.” That’s a strong statement. And the data backs it up-for many NTI drugs, generics work fine.

But not everyone agrees. The American Academy of Neurology still recommends doctors write “dispense as written” on prescriptions for antiseizure drugs. Pharmacists in a 2022 survey said 87% believe generics are effective, but 68% still check with the prescriber before switching an NTI drug. Why? Because they’ve seen the fallout.

Dr. Robert Bies, a pharmacy expert, put it bluntly: “The standard 80-125% bioequivalence limit may not be enough for NTI drugs. A patient switching between two generics could have a 30% fluctuation in drug levels-enough to cause harm.”

Real-World Experience: The Patient Story

Let’s talk about real people.

Sarah, 58, has been on levothyroxine for 12 years. She started on Synthroid. Her doctor switched her to a generic after her insurance denied coverage. Her TSH level went from 2.1 to 6.8 in six weeks. She gained 15 pounds. She felt exhausted. It took two more blood tests and a switch back to brand to fix it.

Mark, 64, took warfarin for atrial fibrillation. He switched to generic warfarin without thinking. His INR (a measure of blood clotting) went from 2.5 to 4.2 in three days. He ended up in the ER with a nosebleed that wouldn’t stop. “I didn’t know switching could do that,” he said. “No one warned me.”

On the flip side, Maria, 41, switched to generic levothyroxine and never noticed a difference. She saved $40 a month. Her doctor said, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Some people do fine. Others don’t. The difference often comes down to consistency.

When Should You Stay on Brand?

If you’re stable on your current medication-brand or generic-don’t switch. That’s the golden rule.

Here’s when you should consider staying on brand:

- You’ve been on the same drug for years and feel great.

- You’ve had trouble with a previous generic switch.

- Your condition is unstable (e.g., recent transplant, uncontrolled seizures, recent stroke).

- Your doctor or pharmacist recommends staying put.

If you’re starting therapy, generics are usually fine. They’re cheaper, FDA-approved, and work for most people. But if you’re already stable? Don’t risk it.

What Should You Do?

Here’s your action plan:

- Ask your doctor: “Is this an NTI drug? Should I stay on the same version?”

- Check the label: Generic drugs list the manufacturer. If your pill changes color, shape, or name, ask why.

- Request “dispense as written”: If your doctor agrees, they can write this on your prescription. This blocks automatic substitution.

- Monitor your labs: If you switch, get blood tests 4-8 weeks later. For warfarin, check INR. For levothyroxine, check TSH. For tacrolimus, check blood levels.

- Report changes: If you feel worse after a switch, tell your doctor immediately. Don’t wait.

Insurance companies push generics because they save money. But your health isn’t a cost center. If your medication is critical, your safety should come first.

What’s Changing in 2026?

The FDA is launching the NTI Drug Registry in 2025 to track real-world outcomes after switches. Researchers are studying 50,000 patients across 15 health systems to see who does well-and who doesn’t. By 2026, we’ll have better data. But for now, the answer is simple: if you’re stable, stay put.

Generic drugs are a win for healthcare costs. But for NTI drugs, consistency beats savings every time.

pradnya paramita

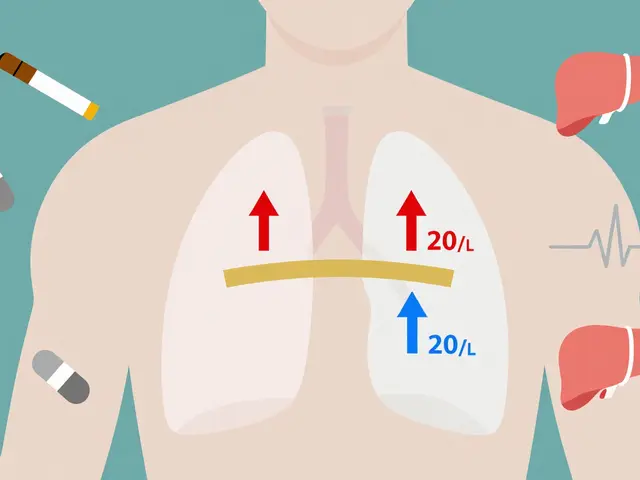

February 3, 2026 AT 20:00From a pharmacokinetic standpoint, NTI drugs demand bioequivalence thresholds tighter than conventional generics-90–111% AUC and Cmax versus the standard 80–125%. The FDA’s 2014 guidance for NTI drugs was a step forward, but real-world variability in gastric pH, P-glycoprotein expression, and CYP450 metabolism can still cause clinically significant fluctuations. A 15% shift in tacrolimus trough levels, for instance, isn’t just a lab anomaly-it’s a rejection risk. We need population-level pharmacovigilance data, not just bioequivalence trials.

Additionally, generic manufacturers often use different excipients. For levothyroxine, lactose vs. mannitol can alter dissolution rates in the duodenum. That’s why some patients on generics report symptom recurrence despite 'normal' TSH. Consistency in formulation matters more than regulatory approval.

Pharmacists should be mandated to log every generic substitution for NTI drugs and notify prescribers. We’re treating these like aspirin, when they’re more like insulin.

Jesse Naidoo

February 5, 2026 AT 05:42You people are overcomplicating this. I switched my warfarin to generic and didn’t even notice. My INR stayed perfect. Stop acting like every generic is a death sentence. It’s just money-grubbing fearmongering.

Zachary French

February 5, 2026 AT 15:42Let me tell you something, folks-this whole 'generic substitution' thing is a corporate conspiracy cooked up by Big Pharma and the FDA to make us pay less while they pocket billions. You think they really care if you have a stroke? No. They care if you stop buying Synthroid. And let’s not forget: the same companies that make the brand also make the generics. Same factory. Same pill. Just a different label and a 90% price drop. That’s not science-that’s capitalism.

I’ve got a cousin who switched to generic phenytoin and ended up in a coma for 72 hours. They told her it was 'just a coincidence.' Coincidence? Nah. It was a calculated risk. They knew people like her wouldn’t speak up. And now? She’s on a feeding tube. And who’s to blame? The system. The FDA. The pharmacy. The insurance company. Everyone but the guy who invented the damn drug.

Don’t be fooled. They’re not saving you money. They’re sacrificing your life for quarterly earnings. And if you think you’re safe because your TSH is 'fine'? Wake up. That number doesn’t tell you if your neurons are firing properly. It doesn’t tell you if your kidneys are screaming. It doesn’t tell you if your liver is giving up.

Stay on brand. Always. Even if it costs your firstborn. You’re not just buying a pill-you’re buying your survival.

Daz Leonheart

February 6, 2026 AT 04:09I get it-switching meds can be scary. But here’s the thing: most people don’t have issues. The ones who do? They’re usually the ones who’ve been on the same brand for decades and then panic when something changes. If you’re stable, don’t switch. But if you’re on generic and feeling fine? Don’t freak out. Your body adapts. It’s not a magic bullet, but it’s not a death trap either.

Focus on what you can control: consistent dosing, regular labs, and open communication with your provider. That’s way more important than the label on the bottle.

You’ve got this.

Samuel Bradway

February 7, 2026 AT 06:06I had a friend who switched from Synthroid to generic and gained 20 pounds. She was miserable. Her doctor said, 'It’s probably not the med.' But she switched back-and lost it all in three months. No one warned her. No one asked if she’d noticed changes. That’s the problem. We treat these drugs like soda, not life-support.

Doctors need to talk about this. Pharmacies need to flag NTI drugs. Patients need to know. It’s not about fear. It’s about awareness.

Caleb Sutton

February 8, 2026 AT 00:05They’re lying. The FDA is in bed with Big Pharma. The 'tighter standards' are a joke. The studies are rigged. They only test 12 people for 14 days. Real people take these drugs for decades. The system is designed to kill slowly. You think your INR is fine? Wait till your spleen ruptures. Then you’ll see.

Jamillah Rodriguez

February 8, 2026 AT 01:09OMG I switched to generic levothyroxine and now I have zits and nightmares. Also my cat stared at me weirdly. Coincidence? I think NOT. 🤨

Susheel Sharma

February 9, 2026 AT 23:14It is a fallacy to assume bioequivalence equates to clinical equivalence. The statistical models employed by regulatory agencies are predicated upon population averages, which are inherently reductive. Individual pharmacogenomic variance-particularly in CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and UGT1A1 polymorphisms-is not accounted for in these trials. A patient homozygous for CYP2C9*3 may exhibit 60% reduced clearance of warfarin, rendering even 'bioequivalent' generics hazardous. Regulatory frameworks are archaic.

Furthermore, the excipient composition of generics is proprietary and often contains allergens or fillers with variable hygroscopic properties. These influence dissolution kinetics in the gastrointestinal tract, especially in patients with IBD or gastroparesis. The current regulatory paradigm is a dangerous oversimplification.

What is needed is a pharmacogenomic registry, mandatory therapeutic drug monitoring upon substitution, and a ban on automatic substitution for NTI drugs without prescriber consent. The status quo is not just inadequate-it is ethically indefensible.

Roshan Gudhe

February 11, 2026 AT 16:47It’s funny how we treat medicine like a vending machine. You insert your insurance, and out pops a pill. But the human body isn’t a machine-it’s a symphony. Every organ, every enzyme, every gut bacterium plays a note. When you swap a pill, you’re not just changing a label-you’re changing the key of that symphony.

Some people adapt. Some don’t. The ones who don’t? They’re not 'anomalies.' They’re messengers. They’re telling us that one-size-fits-all doesn’t work in biology.

Maybe the real issue isn’t the generic. Maybe it’s our belief that we can reduce life to a formula.

Stability matters. Consistency matters. But so does humility. We don’t know enough to say 'it’s all the same.' We should stop pretending we do.

Rachel Kipps

February 12, 2026 AT 20:49I’m a nurse, and I’ve seen patients come in with TSH levels off the charts after switching generics. It’s not rare. It’s not anecdotal. It’s systemic. Doctors don’t always ask about pharmacy changes. Pharmacists don’t always flag NTI drugs. Patients don’t know to monitor. We need better protocols. Not fear. Just better communication.

Katherine Urbahn

February 14, 2026 AT 15:34It is unconscionable that automatic substitution is even permitted for NTI medications! The FDA’s approval process is fundamentally flawed! How can a drug with a therapeutic index of 1.5 be deemed 'bioequivalent' when a 10% fluctuation can result in toxicity or therapeutic failure? This is not a matter of cost-it is a matter of patient safety! We must demand legislative action! Immediate action! No exceptions! No compromises! The lives of thousands hang in the balance!

And don’t tell me 'it’s fine for most people'-that’s the same logic that allowed asbestos in insulation! We must stop normalizing risk! We must stop accepting mediocrity! We must stop trusting corporations with human lives!

Alex LaVey

February 15, 2026 AT 03:24For those of us in the global south, brand-name drugs are often unaffordable. But that doesn’t mean we’re less deserving of safety. The real issue isn’t generics-it’s access. We need global standards for NTI drug manufacturing-not just FDA rules for wealthy countries. A transplant patient in Mumbai deserves the same stability as one in Boston. Let’s fix the system, not fear the substitution.

caroline hernandez

February 15, 2026 AT 23:19From a clinical pharmacy perspective, the data on levothyroxine is overwhelmingly reassuring-multiple meta-analyses confirm non-inferiority. The tacrolimus and phenytoin data is more nuanced, yes, but that’s because of inter-individual variability in CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 metabolism, not inherent instability of generics. The real issue is lack of TDM (therapeutic drug monitoring) infrastructure. If you’re switching an NTI drug, you need baseline and follow-up levels-not a gut feeling.

Also: 'dispense as written' isn’t a magic shield. It’s a tool. Use it wisely. But don’t demonize generics. They’re not the enemy. Complacency is.

Jhoantan Moreira

February 16, 2026 AT 14:37I’ve been on generic tacrolimus since my transplant in 2020. Weekly labs. Strict routine. No issues. I know people who had problems-but they switched without telling their team. The problem isn’t the generic. It’s the lack of follow-up. If you’re going to switch, be proactive. Talk to your team. Track your numbers. Stay informed. You’re your own best advocate.

Justin Fauth

February 17, 2026 AT 07:15Why are we letting foreign factories make our life-saving pills? China and India are printing generics like candy. What if they cut corners? What if they add lead? We’re trusting our lives to overseas labs with zero oversight. This isn’t healthcare-it’s a gamble. We need to bring manufacturing home. Or stop pretending this is safe.

pradnya paramita

February 18, 2026 AT 10:44Re: comment from 7449-your concern is valid, but it’s misplaced. The FDA doesn’t approve foreign manufacturers based on nationality. They inspect facilities-whether in Indiana or Indore. The issue isn’t geography-it’s compliance. And yes, there are bad actors. But the solution isn’t protectionism. It’s better global regulatory alignment. The WHO’s prequalification program and PIC/S collaboration are steps forward. We need more, not walls.